How to Encourage Students to Complete Course Evaluations and Provide Informative Responses

Online Student Feedback Surveys save money, lower staff workload, preserve class time that would otherwise be spent on in-class evaluations, and allow quick data turnaround. However, participation rates suffer, and this reduction in feedback can reduce the accuracy, quality, and constructive nature of student feedback.

Many students believe that faculty do not take evaluations seriously, and do not make changes as a result of the students’ reviews (Marlin, 1987; Nasser & Fresco, 2002; Spencer & Schmelkin, 2002). In fact, when asked, very few instructors report having made changes in direct response to student evaluation input (Beran & Rokosh, 2009). If faculty value course evaluations, educate the students on how they are used, and emphasize to students that their input will be taken seriously, however, there is a positive effect on response rates (Gaillard et. al., 2006). Constructive, informative, and encouraging instructor-student engagement around the course evaluation process is very important in maintaining or improving response rates (Norris & Conn, 2005; Johnson, 2002; Anderson et. al., 2006; Ballantyne, 2003).

When actively promoted and discussed with students, response rates are generally higher than those in courses with little to no instructor attention paid to them. Below are tips for encouraging students to complete course evaluations that provide faculty with constructive feedback.

- Reserve time in-class for students to complete SFS’s. This should garner an equivalent response rate to the previous paper format. *Cue students to bring a device to class, so that they are able to complete the survey (e.g., smartphone, laptop).

- For students who complete the survey outside of class, take a few minutes of class time to show students how to find and use the Course Evaluations system. Demonstrating how the instructions sent to students by email are easy to navigate. A quick demonstration can make a difference.

- Many instructors have found the greatest impact when coupled with the items below. *NOTE: you may not tie the release of grades with completion of evaluations, nor are instructors permitted to give extra credit for completing course evaluations.

- Monitor the response rate throughout the survey window, and immediately after the in-class allotted time for survey completion. Use the real-time response rate to further prompt students to complete their surveys and provide additional encouragement via the tips immediately below.

- Inform students about the purpose of evaluations:

- Explain how the University uses their feedback in merit and promotion.

- Let students know that you will use their feedback to make changes in the course.

- Give students some examples of useful feedback you have received in the past, and how the course/pedagogy has benefited in response.

- Utilize the option in Canvas to add personalized questions to your online evaluation form for any given course (responses to these personalized questions do not get reported and are available to the instructor only).

- Make it an assignment on your syllabus: Listing the completion of the Student Feedback Surveys in the same category as the other course assignments, even if no points are at stake, may help raise response rates. Although faculty members are not permitted to offer extra credit for students to do evaluations, the good news is, you don’t have to! Making an evaluation an assignment, even with no point value attached, raises response rates 7% in one study (Johnson, 2002).

Additional Tips for increasing response rates:

Getting Response Rates to your Course Evaluations Tip 1:

Set aside five minutes at the beginning of class to speak with students about the evaluation process. Mentioning the following can improve your response rates:

- Tell students that the evaluation period has begun.

- Tell students that they will receive emails which will allow them to complete the surveys.

- Log into MyEvalCenter and click the “QR codes” link for your class(es). Print the page that is then displayed and distribute it to your students. Using their mobile devices, they can scan the code and complete the evaluation right in class!

- Give students a few specific examples of how you used feedback from past course evaluations. For example: “Last semester the evaluations said I should make better use of the course website, and that is why this year I have been posting notes online.”

- Tell students that their responses are completely anonymous, and that instructors will only see results after grades are released.

Going over this information at the start of the evaluation period will set the stage for a strong response rate in your class and for the University of Texas at Arlington as a whole.

Getting Response Rates Tip 2:

You can email your students from our system. The email will be sent only to students in all of your classes who have not completed their evaluations. The emails will be anonymous, so you will not know who they are being sent to. This provides an excellent way for students to understand how important it is to complete their evaluations.

We can also automatically send out emails every semester for you. Simply pick when you would like the emails to go out automatically from the drop down menu on the email. If you do not want emails to automatically be sent from you, leave this drop down menu set to “Do not automatically send this email next semester.”

Getting Response Rates Tip 3:

Did you also know that you can add notes in the system about your class? You will see a column on the right hand side of your eval center called “notes.” To add notes to a particular class click the see / add link in this column. Here you can type in any pertinent information about this particular class, what types of activities worked well, what activities didn’t, what you would like to change the next time you teach the course, etc. Click the “save your notes” button when you are finished.

Getting Response Rates Tip 4:

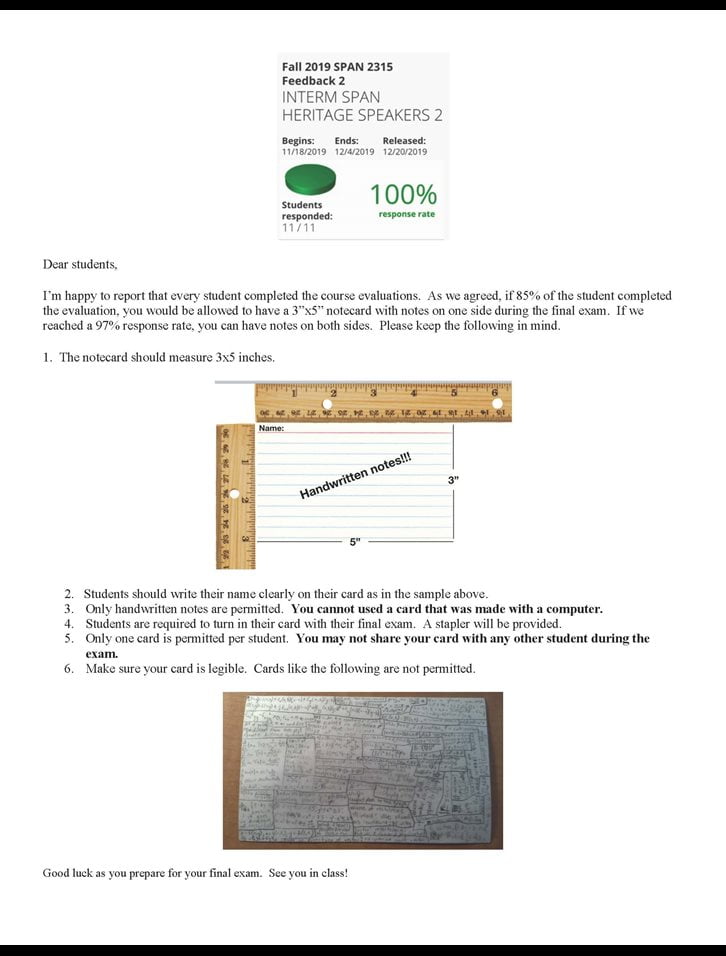

Have you thought about offering incentives? Some faculty do not like reminding students because they feel like they are nagging their students. Group incentives are a great alternative. This allows the students to push their classmates to complete their evaluations. You may use something similar to the following:

‘If this class gets an 80% response rate by the end of the evaluation, I will allow one 3×5 index card of notes to be used during your final.’

One faculty member at UTA used this incentive during the fall 2019 semester and got response rates ranging from 98% to 100%. We recommend faculty member establish a clear set of guidelines for students when completing their note-cards for the exam as in the example posted to Canvas below.

Things to Consider when Interpreting Student Faculty Survey Scores at the Department, College, and University Levels

The following criteria should be considered by committees and individuals who use faculty evaluations to assess the performance of faculty. Consideration of the below are categories that may affect SFS scores due to unconscious or conscious bias that research has shown to be inherent in student evaluations. Due to the variety of elements that come into play, there is no one metric that can off-set any bias.1

- Course modality (face-to-face, hybrid, online)

Online courses might yield lower faculty evaluations than face-to-face courses because of possible difficulties raised by the use of technology (e.g. connection problems).

- Course types (seminar/lecture/lab/studio)

Seminars, labs, and studios have a tendency to be evaluated higher than lecture-based courses because of their relatively small class size and the interactive nature of the course type. In addition, generally speaking, the smaller the class, the higher the variance across terms.

- Course levels (lower division/upper division/MA, MS/ PhD)

Students’ motivation may be greater in upper-division (more specific) than lower-division (more general) classes, which may affect the students’ evaluation of the instructor.

- Class function (prerequisite/major/elective)

Students’ motivation may be greater in elective/major than prerequisite classes, which may affect the students’ evaluation of the instructor.

- Class size (e.g., 7/35/150/300/800)

The larger the class size, the more difficult it is to engage students in the course. Engagement inevitably influences the instructor evaluation. Furthermore, small sample size is highly variable and more extreme.

- Academic discipline

Disciplines engage students differently and therefore comparisons across disciplines should be avoided.

- Team-taught vs. single instructor

Team-taught courses may create challenges for coherence and consistency, as well as confusion about evaluation. For example, if three instructors collaborate on the teaching of a course, it may be difficult to sort out which student comments and assessments correspond with which instructor. In addition, if an instructor is in charge of a large class that includes laboratory sections, teaching assistants may be the ones supervising those labs. A distinction should be made in terms of evaluation of the instructor and evaluation of the teaching assistants.

- Student experience with evaluation process

Lower-division students and new transfer students have less experience with courses than seniors have and this may affect the students’ evaluation of the instructor.

- Student response rate to questions

Low response is not necessarily an indicator of bad teaching; it simply does not allow generalizing results reliably to the whole class.

- Difficult issues or challenging topics

Faculty who teach courses related to cultural diversity and other challenging subjects often receive low evaluations, as do faculty of color who teach predominately Euro American classes.

- Race/Ethnicity/Gender/Sexual Orientation/Age

Research has shown that students’ inherent biases may enter into the evaluation of their instructors.

These guidelines are designed to standardize some aspects of faculty evaluations across the campus and to provide more detailed guidelines for interpreting student evaluation scores to reflect variations among courses being evaluated.

1 These categories are based on San Diego State’s Teaching Task Force recommendations.

References:

Anderson, J., Brown, G. & Spaeth, S. (2006). Online student evaluations and response rates reconsidered. Innovate, 2(6). Retrieved from http://www.innovateonline.info/index.php?view=article&id=301

Ballantyne, C.S. (2003). Online evaluations of teaching: An examination of current practice and considerations for the future. In D. L. Sorenson & T. D. Johnson (Eds.), New Directions for Teaching and Learning #96: Online students ratings of instruction (pp. 103-112). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Beran, T., & Rokosh, J. (2009). Instructors’ perspectives on the utility of student ratings of instruction. Instructional Science, 37(2): 171-184.

Gaillard, F., Mitchell, S, & Kavota, V. (2006). Students, Faculty, And Administrators’ Perception Of Students’ Evaluations Of Faculty In Higher Education Business Schools. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 3(8): 77-90.

Johnson, Valen E. (2002) Teacher Course Evaluations and Student Grades: An Academic Tango, CHANCE, 15:3, 9-16, DOI: 10.1080/09332480.2002.10554805

Marlin Jr., James W. (1987) Student Perception of End-of-Course Evaluations, The Journal of Higher Education, 58:6, 704-716, DOI: 10.1080/00221546.1987.11778294

Norris, J., & Conn, C. (2005). Investigating Strategies for Increasing Student Response Rates to Online-Delivered Course Evaluations. Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 6: 13-29.

Spencer, K. & Pedhazur Schmelkin, L. (2002). Student Perspectives on Teaching and its Evaluation. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 27(5): 397-409.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Weekly or Mid-Semester Evaluations

- Reflective Self-Evaluations

- Peer Evaluations

- Teaching Portfolios, eportfolios, and Teaching Dossier

- Documenting Continuous Improvement in Teaching

- Course Evaluation

- Student Interviews and Exit Interviews

- Assessing Teaching Performance

- Customizing Student Feedback Surveys

- Uniformity in Assessing

- List of References

- Members