FEATURE

STORIES

Turning heads

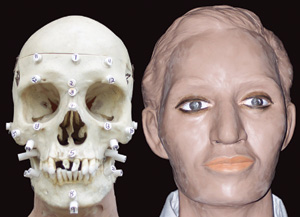

Medical examiners often call on Suzanne Baldon for facial reconstructions to help them solve missing persons cases

Suzanne Baldon helped solve a 40-year-old mystery by reconstructing the face of Kenneth Bennett Glaze, who disappeared near Fort Worth in 1963.

Suzanne Baldon’s early career plans evaporated like a puddle in the Texas sun. The forensic artist and anthropology lecturer wanted to be an art therapist. Instead, she wound through stints as a private investigator, artist, art teacher, park ranger, secretary and college teacher.

Each turn was directed by her passion for art, research and ecology, along with a desire to help others.

“Underlying everything Suzanne does is her overwhelming humanity,” said Dana Austin, forensic anthropologist for the Tarrant County Medical Examiner’s Office, for whom Baldon clay-sculpts facial reconstructions from skulls to help identify missing persons.

One case involved Kenneth Bennett Glaze, who disappeared Aug. 23, 1963, without money or extra clothing, after leaving a Fort Worth restaurant. In a few days his car was found abandoned. Months later, a homicide victim’s skeletal remains surfaced in an unincorporated area of Tarrant County.

The remains were believed to be those of a woman. The police released a sketch of the woman’s probable features, but there was no identification.

For more than four decades, the bones were sealed away in the property room at the Fort Worth Police Department. Then they were turned over to Dr. Austin, who reanalyzed the bones and determined that they were a man’s. After Baldon made a facial reconstruction, a family member identified him, and DNA testing confirmed his identity.

Austin said the mystery probably would not have been solved without Baldon’s help.

“When we have an unidentified victim and call her in, she immediately thinks of the victim’s mother and of the family who doesn’t know if their loved one is alive or dead,” Austin said. “She does not see a skull, she sees a person, and she cares.”

Baldon brings an uncanny combination of skill and intuition to her work, Austin said.

“She is a tremendous portrait artist and understands the human face. With knowledge of facial structure, some aspects of a face are predictable, but others are not. Suzanne has an intuitive sense of what the face was like. When one of her sculptures is compared to a photograph of the victim, the likeness is remarkable.”

Using vinyl eraser refills as tissue depth markers, Baldon identifies specific landmarks on the skull. Each marker has the same location for each skull.

“The tissue depths vary by skull type, sex and estimated size of the individual,” she said.

Early inspiration

Baldon discovered forensic art on the 1970s television show Quincy, M.E. In one episode, Quincy needed to identify a body and brought in Oklahoma forensic artist Betty Pat Gatliff, who was played by an actress on the show. Gatliff studied the musculature and skin depths in the facial area and, through calculated applications of clay upon the skull, reconstructed the features.

Baldon reconstructed the face of "George," a skeleton sent to the United States from india by a medical supply company in 1966. Dallas elementary school students use "George" as a learning resource.

Baldon watched in amazement as the woman’s hands re-created a face. She never dreamed that years later she would study with Gatliff and earn all the certificates of completion offered in forensic art.

She had almost graduated from two-year Kilgore College, but with four toddlers, Baldon’s undergraduate degree was on hold. When her children were old enough to go to school, their mom went to UT Tyler.

Baldon was divorced and shared an apartment with another student, Gail Egbert. A former police officer, Egbert had been seriously injured, unable to resume police work. While studying in Tyler, she worked for a private investigation company based in Dallas. The women planned to come to Arlington after their graduations: Egbert to work for the PI firm and Baldon to get her master’s degree in art therapy at UT Arlington.

Egbert was not a fast typist. Baldon was, so she began assisting with the reports. When Egbert was stricken with cancer and eventually died, the firm asked Baldon to take the job, since, in effect, she had been doing it for several months.

“But I wasn’t Magnum, P.I. I didn’t drive around in a red sports car,” she said. “I sat in an office and did research. I was a third-party objective reporter, just like any researcher.”

Baldon earned her art degree from UT Tyler in 1986, but it was not the triumphant new beginning she anticipated. She came to UT Arlington, without her dear friend, to find that the master’s degree in art therapy had been discontinued. In 1991, as she attempted to “get on with it,” she approached Professor Joseph Bastien in the Sociology and Anthropology Department.

“I sat down and talked to Joe Bastien,” she said, “and I walked out of that room an anthropologist!”

Baldon cares deeply about the environment and decided to do her thesis on the use of public lands. She went to work at Cedar Hill State Park when it opened in May 1991. It was a laboratory for testing her thesis, which analyzed a system aimed at making parks self-sustaining. Ultimately the system didn’t work because “neither the public nor the rangers were ready for it.”

She received her M.A. in anthropology in 1994 and worked as a ranger at the park until October 1995. She applied for jobs related to cultural anthropology in the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, but “the bottom fell out of the money supply and budgets got cut and jobs eliminated.”

– forensic anthropologist Dana Austin on Suzanne Baldon

So she went to work at the Amon Carter Museum in early 1996 and became an adjunct professor at Tarrant County College in 1998, a post she kept after returning to UT Arlington in 2000 as secretary in the Sociology and Anthropology Department. In 2001 she began teaching at UT Arlington during the day, on release time from work, as a volunteer. Then in 2003 she became a lecturer, which means she “walks downstairs to teach instead of dashing over to TCC.”

Face of the future

Other life-changing events occurred during those years. She traveled to Arizona and Oklahoma to study with Gatliff, two decades after learning about her on television. She also studied with Karen Taylor, a forensic artist for the Texas Department of Public Safety, at the Scottsdale Artists’ School. During the workshops, she and her husband, Paul, camped in the Sonoran Desert. By the spring of 1996, she had completed one three-day and four weeklong workshops in forensic art.

Baldon’s children did well in school, found careers they enjoy and have made her a grandmother six times over. In addition to her duties at UT Arlington, she teaches workshops and makes forensic presentations nationally.

The list of cases she has worked on continues to grow. She created a face for “George,” a skeleton used to teach anatomy to a talented and gifted elementary class in Dallas. She also reconstructed the face of a Native American circa 1250 A.D. for a doctoral student at Southern Methodist University. The remains have been “repatriated,” returned to New Mexico and buried. She is working on another Native American who died about 1300 A.D. for the Tarrant County Archaeological Society.

This fall Baldon begins work on a doctorate in transformative studies from the California Institute of Integral Studies. After a week of intensive study in San Francisco, she will complete the work by distance learning.

Then she’ll see what new paths life offers.

— Sue Stevens

Other Stories

Leadership investments

Corporate gifts establish Goolsby Academy scholarship, professorship

Mavericks Personified: Tommy Le Noir

Alumnus brings crime-solving savvy to reality series

The speed of life

Professors’ book examines fast-paced families

Former stars join athletics hall

Ceremony also honors men’s track and field teams

Alumni Association awards scholarships, hosts programs

Search

Contact Us

Office of University Publications

502 S. Cooper St.279 Fine Arts Building

Box 19647

Arlington, TX 76019-0647