FEATURE

STORIES

Nursing education reinvented

Smart Hospital grooms nurses using lifelike patient simulators

After SimMan tells them his chest hurts, senior nursing students work to stabilize his heart rate.

In the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), the sounds of a baby in trouble suddenly fill the room. His lips are turning blue and an alarm rings, indicating falling oxygen levels.

Instinct kicks in, and with a surge of adrenaline, nurses rush to the baby’s bedside. One places an oxygen mask on the infant and attempts to comfort him by rubbing his head. Others, visibly concerned, focus on assessing the problem as the alarm continues to wail.

Nearby, the baby’s mother watches the situation unfold. She screams for the nurses to do something. A social worker tries to calm her.

It is a common scenario in any hospital NICU. But this scene plays out in UT Arlington’s Smart Hospital—a learning laboratory that can create any health care-related scenario the mind can conceive.

Opened in August, phase two of the Smart Hospital is a 23-bed simulated environment in a 13,000-square-foot facility featuring a seven-bed emergency services department, four-bed intensive care unit, two-bed NICU, three-bed pediatric unit, four-bed medical-surgical unit, two labor and delivery suites, a team training room, and a family health and wellness room.

More than 30 full-body patient simulators occupy the space. Half can mimic bleeding, produce heart and lung sounds, give birth to babies and even die. It’s called simulation-based learning, and with it UT Arlington is establishing the most advanced nursing education lab of its kind in the United States.

“We integrate a full array of simulation tools and products into our curriculum—task trainers, static manikins, high-fidelity manikins and even standardized patients, or actors, who play various roles,” said Beth Mancini, professor and associate dean of undergraduate nursing programs. “Simulation is the School of Nursing’s pedagogy—the underpinning of our curriculum.”

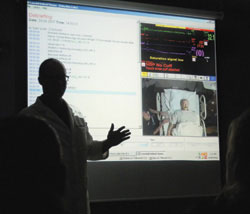

Top: In the control room, nursing faculty create real-life scenarios that require students to react quickly and appropriately.

Center: Senior Hattie Jackson listens to the heartbeat of a patient simulator.

Bottom: In the four-bed intensive care unit, Clinical Instructor Kim Griffith teaches a Senior 1 class about hemodynamics, the study of the properties and flow of blood.

The manikins vary from infants to adults and include 10 SimMan and five SimBaby programmable simulators with chests that can rise and fall. The manikins even have a pulse. Students can intubate (pass a tube down the throat) these “patients,” place them on ventilators, administer CPR and shock them with a defibrillator.

Another eight VitalSim manikins, whose chests do not rise and fall, can be programmed with the same SimMan functions. The simulators can speak and respond to students’ questions with help from instructors in a control room.

Nursing senior Greg Hubbard says the practice he’s receiving will help him adapt to real-life situations that much easier when he graduates in December.

“These manikins can die,” he said. “Their vital signs will change. And even though we’re students in a learning environment, we’re still looking for the best possible outcome. The Smart Hospital is the closest thing we could ask for in getting that hands-on interaction before going into a real clinical situation.”

The remaining static manikins are used to practice fundamental skills like dressing wounds, bathing patients, giving injections and practicing catheterizations. One named Noelle has a mechanical system that simulates the birthing process.

Software programs enhance the experience. FetalSim simulates labor conditions, MicroSim Inhospital enables students to practice computer-based scenarios individually, and Adult and Infant Virtual IV devices teach students to start an IV using minimally invasive techniques.

The Smart Hospital uses a variety of moulage and wardrobe accessories, including wigs, clothes and interchangeable body parts with open and sutured wounds, broken bones and bullet holes. A nuclear, biological and chemical mask can simulate foaming and watering eyes after a bioterrorism attack. Another mask has a metal rod sticking through the cheek and is used for trauma scenarios.

In some simulated clinical interactions, paid actors—called standardized patients—play the roles of patients and family members. When it finally comes time to insert an IV or chest tube into a human patient, students will have practiced on more than 100 task trainers that resemble body parts such as arms and torsos.

Novel nursing

The technology is a far cry from training with oranges, which some programs still use to simulate giving an injection. What makes the Smart Hospital unique is the application of theory and experience.

“Other nursing programs use simulation and running scenarios in their classrooms,” said Carolyn Cason, co-founder of the Smart Hospital and director of the Center for Nursing Research. “But no one is using it the way we are—as an integral part of the learning process and in the context of a large, free-standing hospital environment.”

UT Arlington’s School of Nursing is one of only two nursing schools in the United States (and one of six worldwide) designated as a Laerdal Center of Excellence in Simulation. As it continues to integrate simulation into the undergraduate and graduate curriculum, students will no longer be bound by random opportunity associated with traditional clinical learning.

The Smart Hospital is the closest thing we could ask for in getting that hands-on interaction before going into a real clinical situation.”

- nursing senior Greg Hubbard

Top: Students apply a bag mask to a simulated patient who is having trouble breathing. During the scenario, the patient goes into cardiac arrest, requiring the nurses to perform CPR and use a defibrillator. "He didn't die, so I guess we did OK," one student says.

Bottom: Intensity and emotions run high in the Smart Hospital as students consider the consequences of their actions.

“With simulation, we can ensure all students get the same educational experiences,” Smart Hospital manager Tiffany Holmes said. “For example, we know that every student is going to see a patient with congestive heart failure. But in a real hospital, it’s hit or miss. You may or may not have a patient with CHF the day the students are there.”

It’s that opportunity to experience any scenario on a consistent basis that gives students a deeper understanding of clinical conditions and more adeptness at critical thinking.

“It also creates a more confident and competent nurse entering the work force, one who is able to give safer patient care,” said Mindi Anderson, simulation coordinator and assistant clinical professor.

So where does the classroom environment end and the reality of a hospital begin?

“In order to suspend disbelief and convince the student that we’re not just play acting, we incorporate as many sights and sounds as we can to elicit a sensory response of a patient experiencing a crisis,” said Judy LeFlore, associate clinical professor and director of the Pediatric and Acute Care Pediatric Nurse Practitioner programs. “That includes sounds of the monitors, the smell in the room, as well as the visual appearance.”

Dr. LeFlore, who helps write the scenarios, says they become real because the essence of each room—the entire building, for that matter—pulls you into the hospital atmosphere.

“Many of the scenarios are called low-volume, high-mortality events—those emergencies, such as cardiac or respiratory arrest, that don’t happen all the time and that students are unlikely to experience during their education,” she said. “They may practice for months or even years before they see one of these emergencies. But the Smart Hospital and its technology allow us to create these situations consistently in a lab setting.”

Moreover, each of the hospital’s rooms is monitored from a control center where instructors direct scenarios. Debriefing after each scenario lets students see themselves in action and adjust their responses.

“The first time I’m faced with a similar scenario in a real hospital, I can automatically remember the right course of action to take because I’ve already been through it here,” nursing senior Lanika Tucker said. “And I may never have gotten that repeated experience anywhere else.”

How it all began

The idea for the Smart Hospital came about in 2003 when UT Arlington’s then-vice president for research, Keith McDowell, proposed a combined work force initiative in conjunction with the city and the Chamber of Commerce.

Most of the funding for this first phase of what would become the Smart Hospital—$496,000—came from a Department of Education grant. With continued support from current Interim Provost Ron Elsenbaumer, additional federal grants provided seed money to buy equipment. And by 2004 the School of Nursing had created a Smart Emergency Department, a learning laboratory for undergraduate and graduate nursing students.

In August of that year, the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board called for innovative education proposals. Focusing on the nursing shortage, Dr. Cason wrote a proposal outlining the Smart Hospital as a learning laboratory. But it required partnership with a local community college.

In the debriefing room, students listen intently as Clinical Professor Aaron Mitschke reviews videos to assess how they performed in the scenarios he presented just minutes earlier.

“So I recruited the head of the Nursing Department at McLennan Community College in Waco, which is one of our distant campus sites for one of our programs,” Cason said. “She suggested I contact Jimmy Glover with Laerdal Medical. I told him about the proposal, and within a short time he offered a matching contribution.”

This collaboration would result in the School of Nursing’s designation as a Laerdal Center of Excellence in Simulation.

Without question, the success of the first phase prompted the school to begin planning phase two.

“Phase one was a carve-out,” Cason said. “We used about 7,000 square feet of space in Pickard Hall and outfitted classrooms with the manikins and hospital equipment. But they were still classrooms.”

She said everyone involved knew that phase two would incorporate the kind of care units typically seen in a hospital.

With $500,000 from The University of Texas System ENTER program and a $150,000 grant from the Amon Carter Foundation, the school purchased the Pachl Office and Classroom Annex (west of the music wing of the Fine Arts Building) in August 2006.

With the building secured, the following question was how to renovate and outfit it. Cason said the choice of architecture firm HKS, headed by UT Arlington alumnus Ralph Hawkins, was clear.

“HKS was a key player as we moved forward with the renovation and furnishings of the Pachl Annex,” she said. “And once we purchased the building, we quickly started identifying other collaborators like Hill-Rom.”

What’s next?

The third phase will be a 100,000-square-foot Class C community hospital, the Smart Hospital and Health System (SHHS), built on an undetermined campus site. Now in the fundraising process, the SHHS will be a 60-bed virtual hospital with 60 simulated patients, a site for multidisciplinary health care education and evaluation of clinical competency, work force and product development and health care research.

“It will serve as a learning lab but also as a community resource for taking in overflow patients on an emergency-only basis, such as in the case of a mass-casualty disaster,” Cason said. “That becomes important in cases of disaster preparedness, including natural and man-made disasters.”

To date, the Smart Hospital has been toured by local and national groups and by researchers from as far away as Australia, Bangladesh, Buganda, Denmark, France, India, Japan, Mexico and Norway.

“If you think of health care as an industry, we are light years behind other professions in utilizing the idea of simulation to train our people,” LeFlore said. “Pilots do it, astronauts do it, emergency responders do it. Many medical schools even have large simulated-based learning environments. So why not our nurses, too?”

“UT Arlington is already viewed as a national model,” nursing Dean Elizabeth Poster said. “And it is clear we have the commitment, expertise and collaborative partner support to make our shared vision a reality.”

A reality whose time has come.

— Susan M. Slupecki

Other Stories

Leadership investments

Corporate gifts establish Goolsby Academy scholarship, professorship

Mavericks Personified: Tommy Le Noir

Alumnus brings crime-solving savvy to reality series

The speed of life

Professors’ book examines fast-paced families

Former stars join athletics hall

Ceremony also honors men’s track and field teams

Alumni Association awards scholarships, hosts programs

Search

Contact Us

Office of University Publications

502 S. Cooper St.279 Fine Arts Building

Box 19647

Arlington, TX 76019-0647