| Inside a Washington insider | Teen alum amazes | The singing cancer crusader |

| Home Forethought President's Message Campus Buzz Feature Stories Re:Search The Score Alum News Yesteryear | ||

International radio programs fascinated communication assistant professors Andrew Clark and Tom Christie from the time they were children. That interest has become a focus for collaborative research, with an emphasis on U.S. communication efforts in the Middle East.

Recently, their published works earned them a $10,000 grant to conduct additional research.

Recently, their published works earned them a $10,000 grant to conduct additional research.

One of their articles, “Ready…Ready…Drop!,” was published after Christie and Clark conducted a content analysis of leaflets used by the U.S.-led coalition during the Iraq War. The study focused on analyzing the U.S. government’s attempts to sway international opinion.

The professors discovered three functions of the leaflets: to counter disinformation, to facilitate communication and to effect survival. They correctly predicted that the majority of leaflets dropped among the Iraqi people would contain survival messages.

“These leaflets have a major impact on public opinion because civilian and military casualties directly relate to public opinion,” Dr. Christie said. “The leaflets are designed to reduce civilian casualties, thereby improving public opinion.”

The leaflets contained words in the Iraqi language.

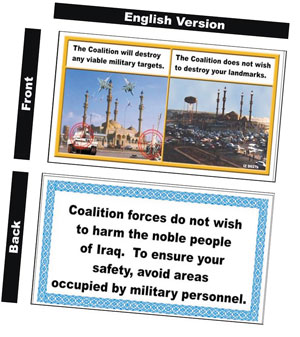

“Coalition forces do not wish to harm the noble people of Iraq. To ensure your safety, avoid areas occupied by military personnel,” one survival leaflet with two photographs said. One of the pictures shows war machinery near a likely target with the caption, “The Coalition will destroy any viable military targets.” The other shows a cityscape with the caption, “The Coalition does not wish to destroy your landmarks.”

Countering what is perceived to be disinformation is often confused for propaganda, Christie and Clark said. The professors say the term propaganda developed a bad connotation only after the Nazi agenda of Germany turned it into a negative label.

“Propaganda is essential at times for foreign policy,” Christie said. “It’s a message that carries an ideological component at a basic level, such as a message supporting democracy.”

In conducting the analysis, the professors faced challenges such as obtaining the leaflets and trying to discover a way to measure their effectiveness. Focus groups and surveys aren’t practical during a war. The grant will allow them to meet their goals utilizing a survey organization operating in Egypt.

Through his work with international broadcasting, Dr. Clark has seen perception differences between Americans and the rest of the world. He has lived in New Zealand and England and traveled the world, observing that most Americans lack access to international broadcasting, which limits their understanding of world events.

“Americans have a worldview that differs from Europeans, who place a lot of emphasis on world studies,” he said. “People there consistently look for multiple sources of news.”

Clark and Christie have also published research concerning the U.S. government’s broadcasting goals in the Middle East through Radio Sawa. They found that Sawa targets a young audience.

Christie and Clark used an illustration with concentric circles to show how the efforts attempt to reach people on different levels. The inner, smallest circle represents survival as the core message. The other two circles exist in ascending size around the smallest circle.

Public opinion is represented by the outer ring, and in the middle rests counter-disinformation leading to the next level of facilitative communication, meaning “the promotion of ideology and image to the affected people or regions,” Clark and Christie wrote in “Winning Hearts: A Framework for Understanding the Use of Facilitative Communication in U.S. International Radio Broadcasts in the Middle East.”

During Christie’s Air Force career, he observed U.S. government international communications in Kosovo. “When I was stationed at Ramstein Air Base in Germany, an airplane was used to broadcast information to the people of the Kosovo region. It parked and took off regularly from right outside my office. It took off every day to broadcast messages much the same as on the leaflets.”

Christie’s association with the military has opened doors to help the duo gather information and possibly assist with the U.S. government’s international communication efforts.

In conducting their research, Christie and Clark realized that leaflet dropping was a mass communication method just as much as broadcasting and that “it was really more about the message than the method.” Christie said that sometimes it’s the best way to send an urgently needed message and perhaps could have prevented some of the tragedies in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

“The lack of effective local, state and national government communication programs in times of crisis may have catastrophic consequences,” he said.

— Kim Pewitt-Jones

| Archives

| Alumni Association |

Giving to UT Arlington | UT

Arlington Home Copyright © 2006 UT Arlington Magazine. All rights reserved. |