| Inside a Washington insider | Teen alum amazes | The singing cancer crusader |

| Home Forethought President's Message Campus Buzz Feature Stories Re:Search The Score Alum News Yesteryear | ||

|

|

“After 20 years, it was time to get out of Washington,” said the amiable Burk, “but we brought our work with us, so it’s not really a true retirement.”

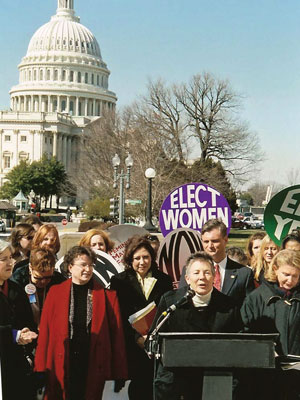

And what a body of work Burk brought—and continues to build. This is the same Burk who until recently served as chair of the National Council of Women’s Organizations, a network of more than 200 national women’s groups collectively representing 10 million women.

In 2003 she led the NCWO charge to open the Augusta National Golf Club to women. She appeared untold times on the national news shows—The Today Show, ABC World News Tonight, CBS Evening News, NBC Nightly News, Crossfire, News Hour with Jim Lehrer. Her print coverage includes The New York Times, People magazine, USA Today and Sports Illustrated. That same year, Ms. Magazine named her Woman of the Year.

And now? On paper, she has an A-list book, Cult of Power: Sex Discrimination in Corporate America and What Can Be Done About It, published by Scribner. She also is the money editor for Ms. Magazine and the editorial director for a book series centered on American political and social movements.

Yet she appears to be about so much more, though she seems almost demure when asked exactly how much.

“I guess you could say I demoted myself,” she said, musing about what’s next in the near future. “I resigned as chair of the national council, but I did keep one project.” Calling it a “melding” of her husband’s lifetime of work in corporate accountability with her own Augusta controversy, the two are examining how the actions of corporate America shape public policy, as well as equal rights in the workplace.

“We’re in danger of losing the gains we’ve made; a lot of forces out there do not believe that women should be equal in career aspirations,” she said. “Educational funding sources are in peril, especially in making inroads for equal education for women.”

Burk’s views took form in the early 1960s, when she was a young married mother of two scrapping it out at UT Arlington for a graduate degree in psychology. Focusing on the then-new field of computer science, she did her dissertation on game theory and became the first woman to earn a Ph.D. at the University, in 1974. She also earned a master’s at UT Arlington in 1968.

“It was an extremely progressive, aggressive, young department,” she said of UT Arlington’s Psychology Department. “I didn’t feel any bias because I was a woman; I would have to say I got the best graduate education one could get at the time.”

But she quickly discovered that, even with their education, female doctoral graduates were not in high demand. She turned to her computer science background and wrote several computer programs, which led to an early career in the field.

That encounter with workplace inequity had lit a fire, however. What started as a quiet avocation became the vocation it remains for her today.

“I’m proud of the work we’ve done so far,” she said, reluctantly. “I think it’s good work, I hope it’s enduring work, but I’m never satisfied.

“Conservative forces want to roll back employment rights, instead of achieving equity in the workplace. Equal wages for women will move a penny or two; the average for women has gone up about a dime in 30 years—64 cents to 74 cents (compared to a dollar earned overall by male wage earners).

“Do we want to wait another generation to close the pay gap?”

It’s questions like these that lead her longtime friend and former UT Arlington student Jerry Cripps to lean toward Burk’s side of the social policy fence, but he adds that it’s her personality that converted many to her way of thinking.

“She’s quick, she’s witty,” he said, “and just a lot of fun to be around. Whether I agreed with her politics or not, I would always want to be her friend.”

Burk asks the pay-gap question—and many others like it—more honestly than rhetorically as she sits in the environmentally friendly house she and Ralph gutted and remodeled with energy-saving materials. She finishes the conversation, taking one last sip of her coffee before beginning her workday.

It’s clear that she does not want to wait another generation—she has five grandchildren—before realizing her dream of equal rights, one that would stretch far beyond the New Mexico mountains she now calls home.

— David Van Meter

| Archives

| Alumni Association |

Giving to UT Arlington | UT

Arlington Home Copyright © 2006 UT Arlington Magazine. All rights reserved. |