Winter 2016: Energy Evolution

From carbon dioxide conversion to landfill mining, researchers at UTA are seeking viable alternative energy options.

Skip to content. Skip to main navigation.

From carbon dioxide conversion to landfill mining, researchers at UTA are seeking viable alternative energy options.

Found in everything from space shuttles to dental fillings, composite materials have thoroughly infiltrated modern society. But their potential is still greatly untapped, offering researchers ample opportunity for discovery.

Within the particle showers created at the Large Hadron Collider, answers to some of the universe’s mysteries are waiting.

Model systems like pigeons can help illuminate our own evolutionary and genomic history.

UT Arlington's tiny windmills are bringing renewable energy to a whole new scale.

The stability of our highways, pipelines, and even manholes is reaching a breaking point.

Scientists believe they have discovered a subatomic particle that is crucial to understanding the universe.

UT Arlington researchers unlock clues to the human body’s most mysterious and complex organ.

UT Arlington researchers probe the hidden world of microbes in search of renewable energy sources.

Wounded soldiers are benefiting from Robert Gatchel’s program that combines physical rehabilitation with treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder.

Tiny sensors implanted in the body show promise in combating acid reflux disease, pain and other health problems.

Nanotechnology researchers pursue hybrid silicon chips with life-saving potential.

Biomedical engineers combat diseases with procedures that are painless to patients.

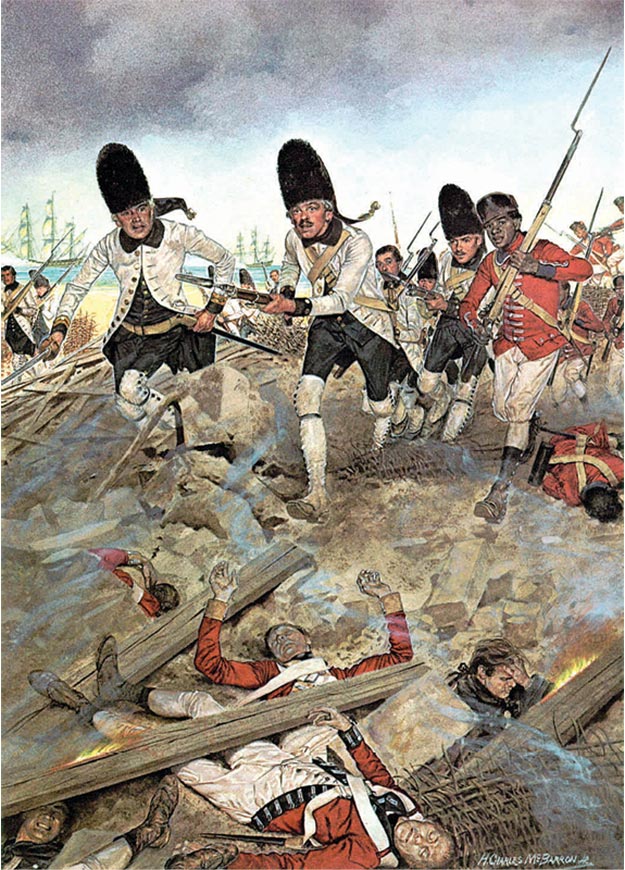

The American Soldier 1780, by H. Charles McBarron, depicts Spanish troops at Pensacola, Florida

When you think of American history, do you ever consider that the British Empire once held the colonies of East and West Florida–or "the Floridas," as they were then called? The 13 colonies, which we are used to viewing as the origins of the United States, were not the only British possessions in North America before American independence.

Through victories over Spain and France during the Seven Years' War (also called the French and Indian War), Britain gained control of the two countries' territorial claims from Florida's Atlantic shore to the Gulf Coast to the Mississippi River. Britain began to colonize the areas before the Revolutionary War, but soon lost control to Spain, which opportunistically joined the conflict after its ally, France, entered on the side of the United States.

From 1779 to 1781, when the English were busy combating the American Continental Army and a host of rebel militias, Spanish forces seized British posts in Baton Rouge and Natchez and captured the ports of Mobile and Pensacola. By overextending its reach into the Americas, then, the British Empire had made itself vulnerable to defeat.

The warfare, diplomacy, and political intrigue tied to these events are the focus of my book, Adventurism and Empire: The Struggle for Mastery in the Louisiana-Florida Borderlands, 1762-1803.

Following wartime defeat, Britain ceded both Florida colonies to Spain through the peace treaty of 1783. But things did not remain quiet for the Spanish or their Southern Indian allies in ensuing years. The United States contested Spain's exclusive claim to the Mississippi and its right to territories far above the Gulf Coast.

This U.S.-Spanish rivalry was not simply a contest between governments. Within the United States, especially in frontier regions, colonial promoters and adventurers were looking to expand their own reach into Spanish and even Indian lands. In some cases, they settled legally within Spanish territory with government permission, taking oaths of allegiance to their new sovereign. In other cases, however, adventurers plotted armed incursions, though such efforts generally failed for lack of U.S. government support and insufficient funds.

One of the most fascinating examples of the latter type of adventurer is William Augustus Bowles, a onetime teenage Tory soldier who fought for the British in Florida, but deserted his unit and found shelter with the nearby Creek Indians. After postwar exile in the Bahamas, Bowles renewed his ties to the Creeks, repeatedly attempted the conquest of Spanish Florida, and in 1799 declared an independent Creek State of Muskogee on the Florida Gulf Coast.

Though Bowles was eventually captured and died in a Havana prison, his exploits demonstrate how private adventurers, acting outside any clear government structure, had a significant role in imperial rivalries during the American Revolutionary era and beyond.

History could have played out very differently if Britain had managed to hold onto the Floridas during the Revolutionary War–most notably, the United States might have then been bounded by former British possessions both in the north (Canada) and south (Florida). The study of such historical contingencies illustrates why history is such a fascinating and essential subject for understanding our world.