Winter 2016: Energy Evolution

From carbon dioxide conversion to landfill mining, researchers at UTA are seeking viable alternative energy options.

Skip to content. Skip to main navigation.

From carbon dioxide conversion to landfill mining, researchers at UTA are seeking viable alternative energy options.

Found in everything from space shuttles to dental fillings, composite materials have thoroughly infiltrated modern society. But their potential is still greatly untapped, offering researchers ample opportunity for discovery.

Within the particle showers created at the Large Hadron Collider, answers to some of the universe’s mysteries are waiting.

Model systems like pigeons can help illuminate our own evolutionary and genomic history.

UT Arlington's tiny windmills are bringing renewable energy to a whole new scale.

The stability of our highways, pipelines, and even manholes is reaching a breaking point.

Scientists believe they have discovered a subatomic particle that is crucial to understanding the universe.

UT Arlington researchers unlock clues to the human body’s most mysterious and complex organ.

UT Arlington researchers probe the hidden world of microbes in search of renewable energy sources.

Wounded soldiers are benefiting from Robert Gatchel’s program that combines physical rehabilitation with treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder.

Tiny sensors implanted in the body show promise in combating acid reflux disease, pain and other health problems.

Nanotechnology researchers pursue hybrid silicon chips with life-saving potential.

Biomedical engineers combat diseases with procedures that are painless to patients.

Photograph by c.j. Burton/Corbis

When the Han River in South Korea blooms a vibrant blue-green, engineers at the Chungju Dam go on red alert. They know the color is produced by an overgrowth of cyanobacteria, a photosynthesizing organism with a reproductive cycle that produces harmful toxins in the river. And since the Han supplies water to more than 25 million people living in Seoul and the surrounding areas, a green sheen tells engineers the public is at risk.

Predicting these algal blooms before they happen is thus crucial to the wellbeing of citizens in that region and others where similar overgrowths occur. Luckily, researchers like DJ Seo are on the case.

In a partnership that spans nearly 7,000 miles, the civil engineering associate professor and his team are working with the Water Quality Control Center of the National Institute of Environmental Research in South Korea to predict algal blooms up to a week before they peak. Given that information, the engineers could, if necessary, release reservoir water into the Han and flush the toxin-laden patches out of the river before they take hold.

Nick Fang

“This is not a water-rich area, so they have to release water optimally in order to conserve resources,” explains Dr. Seo. “Our data, ideally, not only helps conservation, but should also help improve that ecosystem.”

This relationship between engineers in South Korea and researchers at The University of Texas at Arlington illustrates the complexities of water research and its real-world implications. While scientists are entrenched in data, formulas, modeling, and projections, they’re actually doing work that goes well beyond numbers. It goes straight to the heart of the human condition.

In 2010, the United Nations General Assembly enacted a resolution that recognizes water as a basic human right. As its Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights noted, “The human right to water entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible, and affordable water for personal and domestic uses.”

When 11 percent of the global population lacks access to clean water, it’s easy to see the importance of this idea for the international community. But as the potentially catastrophic water shortage in California and the alternating droughts and floods here in North Texas have shown, these issues are just as crucial closer to home.

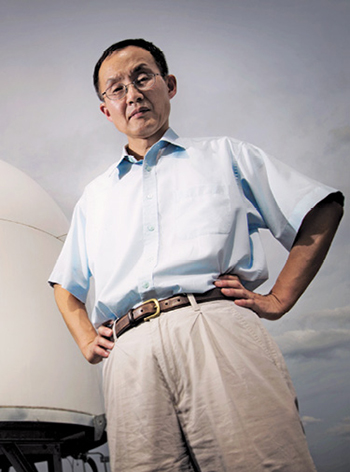

Rapidly growing populations can burden existing water sources both in quantity and quality. Kennedale, Texas, has been feeling the strain and turned to civil engineering Assistant Professor Nick Fang and his students for help.

For the past year, the group has been sampling and evaluating the sediment and stormwater at four locations along the Village Creek watershed, looking for chemicals and elements like cadmium, chromium, lead, copper, aluminum, nickel, arsenic, and more. Their primary focus is on water quality during and immediately after a storm.

A 3-D reconstruction of rainfall from Hurricane Ike produced by Dr. Fang’s research group

“Village Creek feeds into Lake Arlington,” Dr. Fang says. “In order to evaluate the water, we work closely with the city and the Trinity River Authority on storm-based monitoring to see how levels change in response to temperature, time, and weather conditions.”

In the North Texas area, where cities are prone to flash-flooding, understanding why flooding happens, when it will happen, and how to manage it when it does happen is crucial to ensuring a safe and abundant water supply.

“Often, North Texas is an area of climate extremes,” Fang says. “Being able to manage and protect from those extremes is crucial in planning, repairing, and adjusting existing infrastructure.”

For a different project, Fang, who has years of experience at Rice University’s Severe Storm Prediction, Education, and Evacuation from Disasters Center, is evaluating the flood risk of Tarrant County’s floodway levees and the hydrologic impact of land use/urbanization and infiltration on the Fort Worth floodway.

Through such studies, Fang and researchers like him are assisting city planners in addressing what-if scenarios before they become major problems.

“We’re helping the decision-makers make better decisions,” he says.

One of those decision-makers is the City of Arlington, which is facing a monumental choice in the near future. Old sewer lines throughout the city are nearing the end of their life expectancy and will soon start to crack and fail. It’s a pressing infrastructure concern for every region where such water management systems exist, but Arlington is hoping to address the issue before it becomes a problem. The difficulty lies in deciding which pipes to replace first and when to do it.

To that end, the city recently approved a $882,000 contract with UTA engineers to evaluate sewer pipes with a 60-inch or greater circumference.

Dr Ali Abolmaali

To mitigate costs, the University’s Center for Structural Engineering Research and Simulation is using a novel combination of robotic laser equipment and sonar to pinpoint trouble spots in pipelines in their 47-mile surveillance area. After evaluation, the team—led by Ali Abolmaali, chair of the Department of Civil Engineering—will recommend a new, more sustainable and resilient system of fiber-reinforced pipes for the future and help the city prioritize which pipes should be mended or replaced.

“We’ll make recommendations for what to do based on where the robots and sonar detect anomalies within the pipes,” Dr. Abolmaali explains. “This research could provide a blueprint for other cities to copy.”

While Arlington’s sewer system is relatively young compared to many throughout the country, the heavy rain the area received in 2015 had a significant impact on the infrastructure. Buzz Pishkur, Arlington’s water utilities director, says the city experienced significant wall erosion in some areas, including one that caused a collapse. By taking a look at the big picture now, before major problems erupt, Pishkur believes the citizens of Arlington will reap the benefits.

“This evaluation allows us to make more informed decisions about infrastructure replacement,” he says. “That could lead to fewer rate hikes and better use of our capital money. We can pinpoint where to spend the money at a lower cost to residents and with the least amount of inconvenience.”

Like Abolmaali, Seo is also helping the decision-makers. But he’s doing it by traveling back in time via data and modeling.

“It’s called hindcasting,” he explains. “With it, we can go back 30 years and operate, as if in real-time, reservoirs and pipelines with and without the inflow forecast information.”

With this data, Seo can forecast information about precipitation, temperature, and inflow. Such data proves very valuable when water providers must pump water from one system into another. Turning on that pump requires extra energy and costs a lot of money. But with Seo’s help, the providers can make better decisions, which in turn saves energy while maintaining or improving lake levels.

Dr. DJ Seo

Seo’s research has yielded a $283,000 grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Climate Program Office. With this funding, his team is developing an integrated decision support tool that utilizes the Hydrologic Ensemble Forecast Service, developed by the National Weather Service. That agency, the Tarrant Regional Water District, the Trinity River Authority, and the North Central Texas Council of Governments are collaborating on the project.

Currently, Seo is also using a $1.2 million grant from the National Science Foundation to improve the sustainability of large urban areas from extreme weather, urbanization, and climate change. One project under this umbrella is the development of an app that would allow users to report flood conditions in their areas. If the app works the way Seo anticipates, it’s possible the researchers will be able to aggregate thousands of flooding reports. With this crowd-sourced data, he and his team could model urban water systems at a very high resolution, which would enhance data-modeling and allow them to predict upcoming flooding with more lead-time and greater accuracy.

“It is important to recognize that rainfall climatology has been changing significantly,” Seo says. “We have to determine if existing infrastructure can deal with these and future changes that are expected to occur over time.”

But addressing local infrastructure issues has ramifications beyond the immediate area.

“The natural water cycle and the urban water cycle drive the movement of water in DFW, but they are all interconnected,” Seo explains. “The local is connected to the regional, the regional is connected to the continental, and the continental is connected to the global.”

It all leads back to the same idea: Continued—and hopefully improved—access to water for everyone.

“Our goal is pretty simple, ultimately,” says Fang. “If we can learn to manage and plan better, we can always enjoy the water.”