FEATURE

STORIES

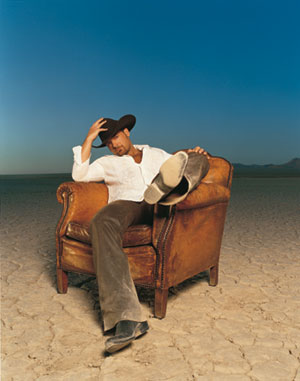

Living the songs he sings

Former student Chris Cagle's talent, looks and charm have earned him three gold records, a cache of top-10 hits and a cult-like following of country music fans.

Photo by Russ Harrington

Chris Cagle couldn’t wait to get to Nashville. He had knocked around Arlington for seven years, waiting tables, selling cars and cable TV, playing music wherever somebody would pay him. Even pledged a fraternity at UT Arlington.

As he sped east on I-30 through Sulphur Springs, he wondered if he’d be able to make a living doing what he loved. Would he ever be good enough to perform at the Grand Ole Opry, country music’s hallowed venue? Could he be the next George Strait or Conway Twitty, who recorded more than 100 No. 1 songs between them.

A siren and flashing lights jolted him back to reality. The officer had already written the speeding ticket when he noticed the contents of Cagle’s jam-packed Chevy truck: clothes, guitar, amplifier.

“What’s the deal?” he asked.

“Going to Nashville,” Cagle replied. “I’m gonna be a star.”

“Tell you what,” said the officer. “You sing me a song, and if I like it I won’t turn in the ticket.”

Cagle flipped down the tailgate and grabbed his six-string Takamine. There, on the side of the interstate, he sang Garth Brooks’ “The Dance,” struggling to rise above the thunder of 18-wheelers. Passersby must have thought they were daydreaming.

It was Aug. 3, 1994. The night before, Cagle and some fraternity brothers went to J. Gilligan’s for a celebratory send-off. Mark Callahan was playing, as he did every Tuesday back then. Cagle’s buddies were loud and persuasive and convinced Callahan to let their hometown hero take the microphone. He crooned the Tim McGraw tearjerker “Don’t Take the Girl.”

“I’ll never forget it,” Cagle recalls. “Out of nowhere, about 30 girls came up on the stage, sitting Indian style, leaning back and forth and singing along with me. And I thought, ‘What a way to go!’ ”

Since his short but spirited college career, Cagle’s life has played like the lyrics to his songs.

Track 01: What a Beautiful Day

"Oh what a feeling, what a wonderful emotion."

Crickets were Cagle’s first Nashville audience. Every morning at 6, he’d take his guitar to the cart barn at the golf course where he worked. The solitude, the acoustics—they were perfect for the budding singer/songwriter. Then he’d throw on his jumpsuit and caddy for country music heavyweights like Grammy-winner Vince Gill and Scott Hendricks, president of Virgin Records Nashville, never mentioning that he wanted desperately to break into their business.

He saved enough money to rent a studio and record four songs: “My Love Goes On and On,” “Laredo,” “Play It Loud” and “Who Needs the Whisky.” At his nighttime bartending job, he slipped them into the CD changer’s random shuffle. “Any time ‘Laredo’ and ‘My Love Goes On and On’ came on, people would just stop down and start listening,” he remembers.

One captivated listener was Donna Duarte, whom Cagle knew only as the wife of a friend. She peppered him with questions: Who wrote the songs? Who’s singing? How’d you get the material?

Cagle told her he wrote them. But he lied and said the singer was a kid he was producing who wasn’t quite ready. Duarte wasn’t satisfied.

Finally Cagle said, “Look, do me a favor and don’t say anything, but that’s me. But I don’t want anybody to know. If you tell people that I sing, all of a sudden every Thursday night I’ll be singing karaoke out the wazoo, and I don’t want to do that.”

Then she dropped the bombshell that changed his life.

“You don’t know what I do, do you?”

He didn’t.

“I’m Scott Hendricks’ executive assistant,” she said, “and I’d like to play this for him.”

Cagle knew Hendricks so thoroughly that he could tell you where he went to college and which songs he’d produced on Faith Hill’s second album. Hendricks also produced Brooks & Dunn and Alan Jackson, two of the most successful acts in country music.

Duarte played the tracks for her boss on a Friday. He called Cagle the following Monday. They had lunch the next day, and by the end of a four-hour meeting, Hendricks was convinced.

“I think you’re just dysfunctional enough to be a superstar,” he told Cagle. “I’m going to sign you to a record deal.”

Cagle went nuts.

“I’m freaking out in front of everybody. All these people are looking at me like, ‘What’s wrong with him?’ And I’m like, ‘I got a record deal, woo-hoo.’ ”

Track 02: Play It Loud

"I wanna dance 'til the break of day."

Three gold albums and six top-10 hits later, Cagle has secured Hendricks’ reputation for scouting country talent. “I Breathe In, I Breath Out” hit No. 1 in 2002, and “Chicks Dig It” reached No. 5 in 2003. Later that year, “What A Beautiful Day” peaked at No. 4 and spent 32 weeks on the Billboard charts.

Cagle won the CMT (Country Music Television) Flameworthy Breakthrough Video of the Year for “I Breathe In, I Breathe Out,” which along with “Laredo” reached No. 1 on the CMT Top 20. His third album, “Anywhere But Here,” debuted at No. 4 on the country charts in 2005.

His fame comes as no surprise to his Phi Delta Theta fraternity brothers. Greg Ticknor remembers trying to hold pledge meetings in fall 1987 while Cagle drummed on anything with a hard surface.

“We absolutely thought he was destined for success. He had rhythm, regardless of what he was doing,” said Ticknor, an Arlington resident who works in the medical supply industry. “He already had his eyes and mind set on Nashville.”

Real estate developer Steve McKeever, who was Student Congress president in 1988-89, will never forget the first outing with his pledge brother. About 25 of them met for breakfast early one morning at a Grandy’s restaurant and, one by one, introduced themselves. When it was Cagle’s turn, he stood on a table and began rapping and beatboxing his life story.

“By the end of the song,” McKeever said, “everybody in the restaurant was clapping.”

Cagle wanted to study music, but his father insisted he study economics. Too often Chris would skip his business courses and sneak into the piano rooms in the Fine Arts Building.

The University’s liberal arts programs and location in the Metroplex—full of nightlife and four hours from his family in Baytown—brought him here. So did the absence of football. Cagle’s ego took a blow when he didn’t receive a scholarship out of high school, so he sought a quality university without a team. The less he thought about football, the easier it was to move beyond the disappointment.

Every Cagle bio mentions where he attended college. A friend once asked why he doesn’t say he went to The University of Texas and leave out the Arlington part.

“I’m like, ‘I went to UTA, man, that’s where I went. I didn’t go to UT. There’s a difference. Be proud of where you went.’ ”

He was so proud that nearly 15 years after his last semester, he took a piece of the University with him on perhaps the biggest night of his life. As TV cameras focused on him as a Top New Male Vocalist nominee at the 2002 Academy of Country Music Awards, his UTA lapel pin shone for millions of viewers.

“It was a really great time in my life,” he said of his days at UT Arlington.

And one of the best times was also one of the most unexpected. As he walked to his dorm one night, loud music drew him to the since-closed Dry Gulch in the basement of the E.H. Hereford University Center. It was Soul Night, not the most popular scene for good ol’ boys with a twang.

The cowboy watched for a few minutes, then plowed ahead. It looked like the line dances he had seen performed to country songs. Actually, it was the Alpha Phi Alpha and Omega Psi Phi fraternities doing step routines. By the end of the night, Cagle’s footwork had won their acceptance.

“That’s my life in a nutshell,” he says. “I kind of get in the middle of it and then ask, ‘Can I be here?’ Usually it’s cool.”

Track 03: Anywhere But Here

"Tomorrow I swear I'm startin' over again."

Cagle is a high-energy performer who writes and produces much of his own material. He has landed six top-10 hits and was an Academy of Country Music Awards Top New Male Vocalist nominee in 2002. Robert Gallagher, entertainment director for Billy Bob’s Texas, says Cagle is among the venue’s most popular acts. Photo: Getty Images/Rusty Russell

Sometimes life is more cruel than cool.

Riding high from his self-titled second gold album, Cagle began having voice problems. Doctors found nodes on his vocal cords and ordered three months of rest. No singing or talking for 90 days for the chatty entertainer. He passed the time shoveling manure on a Tennessee horse farm.

“It was a tough period for me. As a singer, losing your vocal cords can potentially end your career. But fortunately I was able to make a full recovery.”

Then came legal troubles. In 2004 he sued his former manager over publishing and management contracts. Last year a judge ruled against him, but he is appealing the decision.

But the voice ailment and lawsuit were blips compared to the real shocker in 2005 when he learned that he was not the biological father of his girlfriend’s baby.

“As excited as I was about becoming a new father, my disappointment now is equally strong,” he wrote in a statement on his Web site. “Out of respect for all that are involved, please allow this situation to remain private and know that I will not be commenting further on this very personal matter.”

He still doesn’t talk about it, except to say it took him more than a year to rebound. He has learned to be philosophical about his struggles.

“I realize that I’m dealing with people, and people are fallible. I realize that as a person, I am fallible, too. Just as much as I believe that I was wronged, those people probably believe they were justified.

“When you look at the bottom line, I’m a pretty lucky guy. I’m blessed to be able to do what I love doing.”

Track 04: Chicks Dig It

"Lookin' cool in my Superman cape."

In country music, personal drama often breeds artistic success. Cagle is 80 proof positive.

Fans flock to his energetic performances. Called Cagleheads, they are among the most loyal in the industry. At his Billy Bob’s Texas concert in March, they ranged in age from 5 to 75 and included a tiara-wearing thirtysomething with a “Caglehead” sash draped Miss America style across her torso.

“He’s had this following for many years,” said “Crash” Poteet, program director at Dallas’ 96.7 The Texas Twister. “He recruited these Cagleheads through touring, without the help of a MySpace page, which many artists now use to build fan bases.”

On Facebook, the social networking Web site popular among college students, 10 groups have organized around his music. Two are devoted to “Wal-Mart Parking Lot,” his coming of age anthem about life in a small town. Online admirers stretch from Texas to Wisconsin, Tennessee to Pennsylvania, South Carolina to New Jersey.

“A sexy cowboy with great music and an awesome voice. What more can I say?” writes psychology major Sarah Strohacker in her description of the “Crazy About Chris Cagle” Facebook group she started at UT Arlington.

He has been called a “honky-tonk hunk” and “country heartthrob” and was voted one of the sexiest men in country music by CMT and several magazines. It’s a bit embarrassing for an award-winning musician, but he doesn’t complain.

“It’s better than being named one of the top 10 ugliest guys in the business,” he says. “It’s definitely flattering. But I would rather be honored for the music and the live performances.”

His concerts are interactive. Hand him a message and he’ll read it out loud. If your words strike a chord, you may find yourself on stage with him. Good luck keeping up.

“He’s very high energy with a need to feed off the crowd,” says Poteet, who met Cagle during his first radio tour. “The rowdier they get, the rowdier he gets.”

A cliché-prone sportscaster might say Cagle gives 110 percent every time. His goal with each performance: make the audience feel what he feels when he sings.

“I want to reach the guy who’s sitting at the bar with his back to me. Everybody who’s facing me, I’ve already got. I want the people who aren’t.”

Sometimes Cagle’s reach extends beyond barrooms. When he heard about a sergeant killed in combat, he held a meet-and-greet that lasted until 4 a.m. and raised $10,000 for the man’s wife and children. A few days later, 18 of the man’s family members showed up at a concert to say thanks.

Then there’s the story a beholden mom told him at the Indiana State Fair. Her daughter was in a coma following a car accident. For days the child communicated only by humming the chorus to “Laredo,” Cagle’s first top-10 hit. It gave the family hope until the girl recovered.

“That’s the kind of stuff that stops you in your tracks,” he says. “It’s cool to know that somewhere along the line, somehow a guy like me who didn’t have the guts to finish college, a guy who’s kind of lived life by the seat of his pants, who’s done some stupid things, can make a difference in somebody’s life.”

Track 05: When I Get There

"I'll know where I'm going when I get there."

According to Roughstock’s History of Country Music, the genre is the most popular radio format in America, reaching almost 40 percent of the adult population every week. Since 1989, total country record sales have nearly doubled to more than $1.75 billion.

Cagle’s sales are approaching 2 million copies, a number he hopes to surpass with the release—possibly by year’s end—of his fourth studio album. After changes in the industry forced them apart, Cagle and Hendricks are together again, co-producing the new record.

Because of the lawsuit, Cagle accepted music from other writers instead of composing the tunes himself. Couldn’t put his heart and soul into writing, he said, knowing somebody else might own it.

“I feel like I’ve finally proven myself to the big songwriters to where they’ll write with me and write for me. Actually, I’ve been blown away with what we’ve received.”

He’s fiercely loyal to Hendricks for giving him a chance. When Virgin Records Nashville shut down and Hendricks got fired, Cagle still wanted to make him proud. He could feel the record exec watching, he just didn’t know from where.

“Sometimes you second-guess or doubt your writing just because of basic insecurities that you deal with as a person,” Cagle says. “That’s the way I was as an artist for so long. I was deathly afraid to go on stage. For whatever reason, when Scott Hendricks said, ‘I’m going to pull the trigger on you,’ that validated me as a person. From then on, I was never afraid.”

Cagle is viewed as a versatile artist—expressive voice, good looks, Southern charm—who can score hits with both ballads and boot-scooters. McKeever calls him a good-hearted guy in a selfish industry who hasn’t lost track of who he is.

Ditto, says Poteet. “He’s a great guy who will talk your ear off about everything from music to sports to politics. I remember he took my young stepson to the side and spent a good 15 minutes giving him advice on staying positive and working hard to achieve success.”

When discussing his own success, the 38-year-old Cagle shoots straight.

“I’m not the most successful guy in country music, but I’m not at the bottom of the barrel, either. I’m somewhere in the middle. Am I satisfied with that? No. I’m not just happy to be here. If I was just happy to be here, I’d quit.”

These days he seeks balance. He wants to improve not only musically but in all aspects of his life. When he looks ahead and behind, he wants to be unashamed of what he has or hasn’t done.

“At the end of my shows and in the things I write in my records, I always say, ‘I’ll see you when I get there.’ I don’t know where ‘there’ is, and I don’t know if I’ll ever make it.”

But you sense that he’ll never stop trying.

Bonus Track: Hey Ya'll

"Said officer, what have we done wrong?"

Eight years after that initial drive to Nashville, Cagle played the civic center in Sulphur Springs. As he mingled with fans following the concert, a uniformed man approached.

“I’ve got a warrant for your arrest for failure to appear,” he said.

He was joking, right?

“Wait a minute, is this for Aug. 3, 1994?” Cagle asked.

“Yes, a speeding ticket,” said the sheriff, who wasn’t smiling.

“But the officer liked my song. He told me he wasn’t going to turn in the ticket,” said Cagle, who recounted the tale of his unconventional roadside serenade, eventually convincing the sheriff to drop the charges.

He hadn’t thought about the incident since he’d arrived in Nashville, hadn’t reflected much on those early dreams. Some had come true. He had recorded a No. 1 hit, far short of George Strait and Conway Twitty numbers, but one more than many country singers. And he had played the Grand Ole Opry.

“It’s like going to high school, and there’s that one chick everybody wants to date,” he said of his first Opry performance. “You’re the dork, yet somehow you wind up going to the prom with her. You’re like, ‘I can’t believe I’m here.’ ”

He was. And the chicks dug it.

IN TUNE with CHRIS CAGLE

Born: Nov. 10, 1968, in DeRidder, La.

Grew up: Baytown, Texas

Lives: Nashville, Tenn.

Odd jobs: nanny for three girls, bartender,

car salesman, golf caddy (once caddied for Michael Jordan)

Hobbies: cooking, raising performance quarter horses at the Babcock Ranch

in Gainesville, Texas

Childhood memory: His dad wouldn’t let him listen to rock ‘n’ roll, so young Chris made up lyrics from the Bible to the rock songs he played on his guitar.

Discography: “Play It Loud” (2000), certified gold; “Chris Cagle” (2003), certified gold; “Anywhere But Here” (2005), debuted at No. 4; working on a fourth album

Musical tastes: Charlie Daniels, Conway Twitty, George Strait, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Journey, .38 Special, Fleetwood Mac, The Eagles, Carole King, James Taylor, Al Green, Otis Redding

Manager: Doc McGee, who has managed KISS, Motley Crue, Bon Jovi, Diana Ross and James Brown. McGee told Cagle, “You [playing] live is one of the best things I’ve seen in country music since Garth Brooks.”

On songwriting: “When something happens in my life that makes me feel something—moves me to anger, happiness, joy, sorrow, whatever—I’ll take that emotion and commercialize it.”

On “Miss Me Baby”: “I wrote it out of vengeance. It was one of those situations where I hoped that whoever she dates next can’t get it right, and she just thinks of me.”

On his upcoming album: “Now that Scott [Hendricks] and I have gotten a chance to get back together, the fire is lit. We’re both chomping at the bit.”

Web site: www.chriscagle.com

— Mark Permenter

Other Stories

Partners in discovery

Quality Enhancement Plan's pilot projects to launch this fall

Mavericks Personified: Willie Hernandez

Former Movin' Mavs star shoots for success in the wheelchair industry

Learning to serve

Many UT Arlington courses require students to perform community service. For those who enroll, it can be a life-changing experience.

Education, family style

Using their UT Arlington degrees as a foundation, the Ponce siblings fashioned successful careers in law, teaching, computing, engineering and journalism.

Morrow selected to lead women's basketball program

Contact Us

Office of University Publications

502 S. Cooper St.279 Fine Arts Building

Box 19647

Arlington, TX 76019-0647