FEATURE

STORIES

A legacy of honor

A building, a street and a recognition society bear his name, but former President Wendell Nedderman says he'd rather people remember him as a man of principle.

At 85, Wendell Nedderman is still the unassuming Iowan with the Texas-sized voice and unassailable presence, the undeniable Maverick with an immeasurable devotion.

July marks 15 years since his retirement, which ended the longest presidential tenure in University history. He managed growth and change on almost every corner, laying the foundation for the sprawling research university that UT Arlington has become.

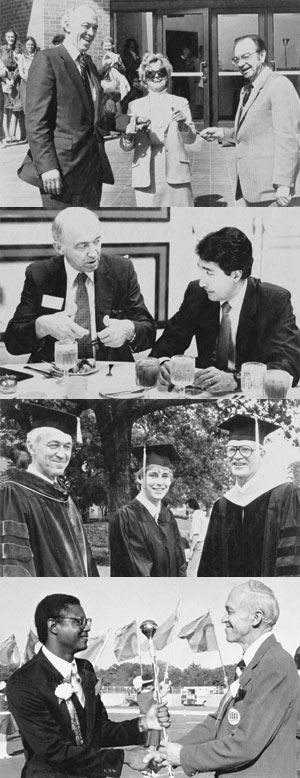

From top: Dr. Nedderman, former nursing Dean Myrna Pickard and Tom Vandergriff at a ribbon-cutting ceremony for the Nursing Building. During Nedderman’s 20-year presidency, the University constructed 24 buildings. • Nedderman talks with Henry Cisneros, former mayor of San Antonio and U.S. Housing and Urban Development secretary. • First as dean of engineering, then as president, Nedderman participated in dozens of UT Arlington commencement ceremonies. • Nedderman congratulates Rodney Lewis, the 1980 Homecoming king. Photographs courtesy of Special Collections, UT Arlington Library.

He served 20 years as UT Arlington’s president (1972-1992). After 10 years as engineering dean, he served as vice president for academic affairs and simultaneously held such positions as graduate school administrator and vice president for research and graduate affairs. In 1992, he was named president emeritus and received the Mirabeau B. Lamar Award for leadership in learning by the Association of Texas Colleges and Universities.

His legacy is so transcendent, he’s now a Wikipedia entry. Students not yet in grade school when he retired attend class in Nedderman Hall and park along Nedderman Drive. The University’s philanthropic employees are members of The Nedderman Society.

It is all much ado about a man so grounded that, for the first 17 years of his presidency, he didn’t even keep a reserved parking space on campus.

But truth is, it was Wendell Nedderman who built UT Arlington. This was a speck of a school when he arrived in the 1950s; as president he constructed 24 buildings, implemented 64 degree programs (44 on the graduate level) and nearly doubled enrollment. With Dr. Nedderman at the helm, UT Arlington went from burgeoning to bursting at the seams.

“President Nedderman was totally committed to the University, its development, and its students, and was a zealous advocate for all three,” Dean of Libraries Gerald Saxon wrote in Transitions, his published history of UT Arlington. “For 20 years … he acted in what he considered the best interests of the University.”

Same story 15 years later. Nedderman still visits the campus, still follows UT Arlington headlines and still remembers a time in office that, he said recently, “seems like it was almost yesterday.”

‘I’m a growth man’

In 1959 Arlington State College (now UT Arlington) tabbed Nedderman, then a tenured professor at Texas A&M University, to lead its new College of Engineering. For a man accustomed to the unfailing certainties of engineering, it was a leap of faith.

“I’ll tell you that in 1959, there wasn’t much on this campus,” he said. “In fact, I spent three sleepless nights before I decided to come.”

But what ASC lacked in pizzazz, it made up in potential. Nedderman ultimately came to Arlington, he said, because “I didn’t see how this thing could miss, located right between Fort Worth and Dallas.”

To make sure it didn’t, he went to work recruiting the faculty and staff who would build the engineering college. A year later, they moved into the largest classroom building in the Texas A&M System (which this institution was a member of at the time), now named Woolf Hall in honor of then-President Jack Woolf. By the end of the decade, ASC’s engineering school had five accredited undergraduate programs and its first graduate degree programs. A Ph.D. in engineering, the institution’s first doctoral program, was approved in 1969.

“We considered this a real achievement,” Nedderman recalled. “We were very much in a growth mode, and I am a growth man. … I was a very privileged individual to hit things just at the right time.”

For the next decade, Nedderman helped grow the engineering school into one of the Southwest’s best before becoming vice president for academic affairs under President Frank Harrison, who had succeeded Dr. Woolf. When Dr. Harrison left abruptly in 1972, UT System Chancellor Charles LeMaistre named Nedderman acting president.

Though intended to be a temporary appointment, Nedderman said he wanted to do things like he would be president for the next 20 years.

How prophetic that remark would be.

‘Great aspirations for the University’

Nedderman graduated first in his high school class and enrolled in Iowa State University’s civil engineering program. He earned his bachelor’s degree in 1943 and joined the Navy Reserve, eventually earning eight battle stars and three campaign ribbons as a commissioned officer aboard the destroyer USS Patterson. Before he was 23, Nedderman had fought in the Marianas, the Philippines, on Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

Despite his military exploits, his destiny was in academe. When the war ended, he completed his master’s degree at Texas A&M and his Ph.D. at Iowa State. He was 38 when Woolf called in 1959. Reservations notwithstanding, Nedderman couldn’t resist the chance to start an engineering college. And he noted that Woolf had “great aspirations for the University—I learned a lot from him.”

“It’s amazing what you can find out by listening. I discovered early in the game that faculty members could gracefully take ‘no’ for an answer if you heard their point of view and if you told them why you arrived at the decision you did.”

– UT Arlington President Emeritus Wendell Nedderman

That philosophy of pride and optimism became the hallmark of Nedderman’s presidency. He once declared that UT Austin might be the flagship of the UT System, but UT Arlington was its crown jewel.

“You have this diverse group of alumni, legislators, regents, faculty, staff, students, all sometimes tugging in different directions,” he said. “You have to pull them all together with a feeling of great pride in your university. And I think there is no substitute for taking pride in your university and exhibiting great enthusiasm.”

His enthusiasm proved genetic—three sons, two daughters-in-law and one granddaughter (currently on the volleyball team) all attended UT Arlington—and contagious. Nedderman calls the greatest achievement of his presidency “recruiting many really outstanding faculty members who had a shared vision of what UTA could be all about.” His door was open to anyone who needed his time, and he believed in academic freedom at any cost.

“I believed in treating everyone with dignity, whether they deserved it or not,” he said. “I never held a grudge, and I think I could have come up with a number of reasons for holding a grudge in my career. I figured holding a grudge would hurt me more than it hurt anybody else.”

When feuding colleagues in one department refused to work together, Nedderman and W.A. Baker, his vice president for academic affairs, sequestered them in a conference room for 4½ hours. “We said, ‘Let’s go at it,’ ” Nedderman remembered. “They didn’t leave that room until 6:30, and by then they went out the door laughing. Earlier they were ready to kill each other, and now they go out laughing.”

In that situation and in others like it, Nedderman said, the key was listening.

“It’s amazing what you can find out by listening. I discovered early in the game that faculty members could gracefully take ‘no’ for an answer if you heard their point of view and if you told them why you arrived at the decision you did.”

If only listening could solve every problem Nedderman faced.

‘We had to scramble and claw’

Nedderman inherited from Woolf and Harrison a rapidly developing university. Woolf began the Graduate School in 1966, and Nedderman focused on its expansion. The Ph.D. in engineering, which came on Harrison’s watch, had launched UT Arlington down the path to research institution, and Nedderman held to it.

Even when some higher-ups didn’t agree.

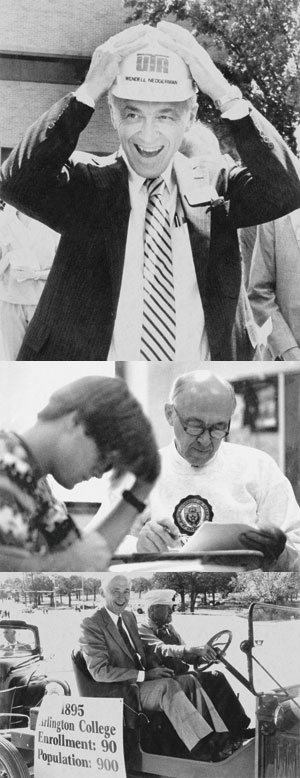

From top: A self-described growth man, Nedderman not only engineered a huge physical expansion of the campus but oversaw the implementation of 64 degree programs, 44 at the graduate level. • Nedderman plays undergraduate for a morning during the 1990 Big Switch, an event in which the president and a student trade places. • Nedderman takes one of the first rides down Cooper Street after it was lowered to accommodate pedestrian bridges in 1990. Photographs courtesy of Special Collections, UT Arlington Library.

“The coordinating board didn’t like the idea of degree proliferation. They didn’t want duplication. North Texas had a Ph.D. in chemistry; well, then, we didn’t need one. UT Dallas had a Ph.D. in physics, so therefore we didn’t need one. You had to work around that. There was the challenge. We had a commissioner of higher education who believed in holding the line. We had to scramble and claw for every degree program we got. None of them ever came easy.”

As the University began adding more degree options—thus attracting more faculty, staff and students—it needed more space. But obtaining construction funding was no easier than getting degree programs.

“They used to tell me that a university is about people, not about bricks and mortar,” Nedderman said. “And I said, ‘Sir, I couldn’t agree more. But these people need adequate facilities to teach in. And our students need adequate classrooms to learn in.’ I’m not talking about bells and whistles here. I’m talking about basic physical needs.”

Nedderman’s challenge was so daunting, he recalls a Texas College Coordinating Board member bristling at a proposed construction project because it was illustrated in color. “All he did during the whole meeting was look at the color and say, ‘This looks like a gold-plated Cadillac to me!’ ”

After that, business affairs Vice President Dudley Wetsel considered requesting that all artist renderings be done in black and white.

‘What’s best for the University’

UT Arlington had played football for almost 80 years, including winning two junior college national titles in the 1950s, when Nedderman disbanded the program following the 1985 season. He calls it the hardest decision he ever had to make. It’s a decision he stands by today, but one he doesn’t talk much about.

UT Arlington was hardly a football powerhouse by the time Nedderman took office. Fans didn’t follow the team off campus when it moved to Turnpike Stadium (later renamed Arlington Stadium and home of the Texas Rangers). For the first 13 years of his presidency, Nedderman tried to make the program viable, even building a $7 million stadium on the west side of Davis Drive.

But Maverick Stadium, which seats 12,000, was seldom even half full, and Maverick athletics teams were losing so much money, they were propped up by funds intended for academics and research.

“Our football program was bleeding all our other sports dry,” Nedderman told The Shorthorn in 2003. “We weren’t very good at anything. And if no one wants it, why have it when it’s damaging everything?”

If some were surprised by Nedderman’s decision to drop football, others hardly noticed. Political science Associate Professor Allan Saxe recalled in Transitions that “70 percent [of the student body] would say they are not heartbroken over dropping football. Ten percent are heartbroken, and the remaining 20 percent did not know UTA even had a team.”

Nedderman guaranteed coach Chuck Curtis’ contract and the players’ scholarships. And he implored those who threatened to turn their back on UT Arlington: “Rally behind our remaining sports and help us fund them fully. … To those alumni who say, in the emotion of the moment, that they will withdraw all support to their university without football, I beg you to reconsider. Surely your university transcends football. … Let us all join together. The past is the past. A great future for our university lies ahead.”

Without football consuming more than half the athletics budget, the other teams began to flourish. Since football was dropped, the volleyball team has made the national semifinals, women’s basketball has reached two NCAA tournaments, baseball and softball have had postseason success, and every sport has won a Southland Conference championship.

“There are many things I would have done differently during my presidency, but I’ve never regretted this move,” Nedderman told The Shorthorn. “If, some day, it turns out a program can come about that’s viable, I say bravo. But I’m not sure when that will be.”

Robert Witt, UT Arlington’s president from 1995 to 2003, is now president at the University of Alabama, one of the nation’s most passionate football universities. He believes Nedderman’s decision to drop football was not only right, but courageous.

“With Wendell, it was never about what was best for Wendell. It was always what was best for UTA,” Dr. Witt said. “If every president in the country wanted to write a phrase and put it in his or her wallet and look at it every day, it should be that it’s never what’s best for the president and always what’s best for the university.”

‘My greatest legacy’

UT Arlington has had four presidents since Nedderman retired in 1992. He says he has been careful not to interfere.

“With Wendell, it was never about what was best for Wendell. It was always what was best for UTA. If every president in the country wanted to write a phrase and put it in his or her wallet and look at it every day, it should be that it’s never what’s best for the president and always what’s best for the university.”

– former UT Arlington President Robert Witt

“My attitude with the presidents who followed me was always I know my place as a former president, and I’m willing to help in any way I can. But you’ll have to ask me. I’ve been asked a number of times, and I’m always happy to help.”

Witt called him an adviser, particularly in the beginning.

“In my first year, he was very generous with his time and helped me understand the institutional history of UTA. … Never once did he try to lobby me in a separate direction, but he was always there when I called him. He was the ideal predecessor for me. When I retire, I want to be the type of retired president he was. That will be my tribute to him.”

UT Arlington’s current president, James D. Spaniolo, said Nedderman helped him “understand the distinctive culture of UT Arlington.”

“I deeply appreciate his advice, his wise counsel and his friendship,” Spaniolo said. “Wendell Nedderman has been a steady influence on this university for almost 50 years. He is the quintessential Maverick and a true UT Arlington treasure.”

While Nedderman is proud of the UT Arlington he helped build, he believes that what has happened in the last 15 years is just as impressive.

“What I saw was continuing to build beautiful facilities that would accommodate faculty, staff and students, new degree programs, ever increasing the reputation of UT Arlington,” he said. “I see a better university that gets better every year. I feel pleased with the state of the University at the present time. This is, in some respects, still the beginning. I think we still have great days ahead for UT Arlington.”

As for him?

“Somebody asked me once … what do I consider my greatest legacy? My greatest legacy is that I was an honorable man.”

It’s a legacy you can’t build with bricks and mortar.

— Danny Woodward

Other Stories

Partners in discovery

Quality Enhancement Plan's pilot projects to launch this fall

Mavericks Personified: Willie Hernandez

Former Movin' Mavs star shoots for success in the wheelchair industry

Learning to serve

Many UT Arlington courses require students to perform community service. For those who enroll, it can be a life-changing experience.

Education, family style

Using their UT Arlington degrees as a foundation, the Ponce siblings fashioned successful careers in law, teaching, computing, engineering and journalism.

Morrow selected to lead women's basketball program

Contact Us

Office of University Publications

502 S. Cooper St.279 Fine Arts Building

Box 19647

Arlington, TX 76019-0647