Winter 2016: Energy Evolution

From carbon dioxide conversion to landfill mining, researchers at UTA are seeking viable alternative energy options.

Skip to content. Skip to main navigation.

From carbon dioxide conversion to landfill mining, researchers at UTA are seeking viable alternative energy options.

Found in everything from space shuttles to dental fillings, composite materials have thoroughly infiltrated modern society. But their potential is still greatly untapped, offering researchers ample opportunity for discovery.

Within the particle showers created at the Large Hadron Collider, answers to some of the universe’s mysteries are waiting.

Model systems like pigeons can help illuminate our own evolutionary and genomic history.

UT Arlington's tiny windmills are bringing renewable energy to a whole new scale.

The stability of our highways, pipelines, and even manholes is reaching a breaking point.

Scientists believe they have discovered a subatomic particle that is crucial to understanding the universe.

UT Arlington researchers unlock clues to the human body’s most mysterious and complex organ.

UT Arlington researchers probe the hidden world of microbes in search of renewable energy sources.

Wounded soldiers are benefiting from Robert Gatchel’s program that combines physical rehabilitation with treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder.

Tiny sensors implanted in the body show promise in combating acid reflux disease, pain and other health problems.

Nanotechnology researchers pursue hybrid silicon chips with life-saving potential.

Biomedical engineers combat diseases with procedures that are painless to patients.

Photograph by Blend Images

From Norman Rockwell paintings to People Magazine’s “baby bump” updates, modern Western culture has long been fascinated with pregnancy and birth. In fact, having biological children is viewed as so important that both the U.S. Supreme Court and the United Nations have upheld the practice as a basic right of man. But procreation isn’t always easy, especially as couples increasingly delay starting a family in favor of their careers. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 12 percent of American women of childbearing age struggle with infertility—the key word being struggle. In a 2015 survey conducted by the Reproductive Medicine Associates of New Jersey, more than half of the people who had experienced infertility said they found it more stressful than both unemployment and divorce.

Still, reproductive medicine is booming. The highly profitable but largely unregulated field is thought to generate $3 to $4 billion a year in the United States alone.

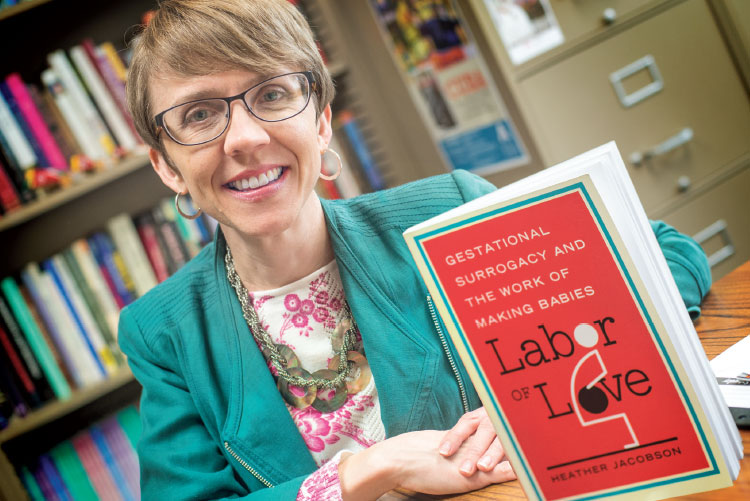

“I liken it to an infertility train,” says Heather Jacobson, associate professor of sociology and author of Labor of Love: Gestational Surrogacy and the Work of Making Babies (Rutgers University Press). The book is the first full-length look at gestational surrogacy in the United States. “If you’re on the train, it’s really hard to get off because one form of treatment leads to the next, and the next, and the engine just keeps pushing along.”

But all those treatments are expensive. So when North Americans get priced out of the market, they sometimes look to cheaper destinations in the hopes of finally creating a family. Amy Speier, assistant professor of medical anthropology, examined the experience of those traveling to the Czech Republic for less expensive infertility treatments in her book, Fertility Holidays: IVF Tourism and the Reproduction of Whiteness (NYU Press).

In modern traditional surrogacy, which began to be commercialized in the mid-1970s, the surrogate’s own egg is artificially inseminated. Today, however, most couples opt for gestational surrogacy, in which intended parents use their own egg and sperm (or donated egg and/or sperm). This change is thought to be due to the potentially problematic questions about parenthood that traditional surrogacy can introduce—something brought harshly into the spotlight with the Baby M case in 1986, in which surrogate Mary Beth Whitehead changed her mind about giving up her biological daughter after the baby’s birth, despite a signed contract to do so.

Surrogacy is unregulated and unmonitored at the federal level in the United States, though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services do monitor and collect data about the procedures and drugs used in assisted reproductive technologies. A few professional medical associations, such as the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, offer guidelines, but they are voluntary. State laws vary, with some allowing commercial surrogacy, others—like Texas—permitting it only for married couples, and yet others banning it outright. Worldwide, laws are similarly mixed, but the majority restrict payment for surrogates.

Heather Jacobson’s Labor of Love is the first book-length ethnographic survey of surrogacy in the United States

Of the nearly 4 million babies born every year in the United States, only 1,500 are thought to result from surrogacy. That’s barely a drop in a sea of blue and pink booties, yet surrogacy, as Dr. Jacobson examines in Labor of Love, has attracted an inordinate amount of attention, much of it negative or sensationalized. The cultural backlash against surrogacy—which critics paint as “unnatural”—largely stems from societal discomfort with what Jacobson describes as the “overlap between family and commodification, work, and the world of money.”

However, she believes that gestational surrogacy raises more complex issues than natural vs. unnatural, as the practice of surrogacy is carefully framed by all involved to make it more culturally palatable—which, in turn, keeps the industry viable.

As she waded into the world of surrogacy, Jacobson found that a number of informal rules had been enacted that revolved around money. In the United States, agencies look for “wholesome” women who don’t appear to be financially motivated. Of the 31 surrogates she interviewed between 2009 and 2012, most were married and from the lower or middle classes. Further, all had children of their own. Nineteen worked outside the home while serving as surrogates, mostly in female-dominated professions like teaching or nursing, while nine described themselves as stay-at-home moms.

“By framing surrogacy as a gift given to truly needy infertile couples by warmhearted, financially stable, loving mothers, surrogacy market players are attempting to manage the impression of surrogacy,” Jacobson writes.

Most surrogates today are paid—first-timers can make $15,000-$25,000 while experienced surrogates often receive $20,000-$35,000—but Jacobson found that the women in her sample were socialized to downplay the compensation they received. They also were extremely reluctant to characterize what they did as “work,” despite the medical procedures they endured, the health risks they faced, and the general upheaval to their and their families’ lives. To them, work was something one was forced to do; surrogacy, on the other hand, brought pleasure because they genuinely enjoyed being pregnant.

But Jacobson argues that this framing ends up obscuring the time-consuming and difficult labor surrogates engage in. She notes that such rhetoric also aligns surrogacy with other forms of care work that women mainly perform in the market—work like nursing, teaching, social services, and social work—that is seen as unskilled and that doesn’t garner much respect, which in turn keeps wages low.

Despite cultural concerns over what surrogates earn, their fees make up just a fraction of the price for intended parents, who are responsible for all expenses. An in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle costs on average $12,400, but medications and related procedures can double that figure; an attorney costs as much as $12,500; and an agency up to $20,000. With IVF success rates topping out at 43 percent (but falling as low as 13 percent for those older than 40), a successful surrogacy journey can cost $150,000 or more.

Thus, commercial surrogacy—like many of today’s reproductive technologies—becomes only available to those with money.

After struggling to conceive, “Hana” and her husband were told by their Ohio doctor that they needed to do IVF if they wanted to have a child. It’s a familiar story in the infertility world, and one that usually ends with the couple realizing they can’t afford the procedure. But unlike many, Hana knew of an alternative. She traveled to the Czech Republic, where she underwent state-funded IVF and conceived twins on the first try.

Given the country’s lower price structure, Hana quickly realized there was a business opportunity there. In 2006 she and her husband began arranging “IVF holidays” through their website. Photographs of European castles attested to the vacation aspect of a trip, while a photo of her smiling daughters demonstrated the success one could achieve abroad.

But perhaps most importantly, Hana—and another broker who soon set up shop—tapped into something vital that was missing from the American market: care.

By the time couples reach IVF, often after months or years of trying fertility drugs and intrauterine insemination, many report disenchantment with the American medical system. They’ve spent thousands of dollars, with nothing to show for their efforts, and that failure colors their perceptions.

“They lose faith in North American doctors, who are seen as profiting from their inability to conceive,” Dr. Speier writes in Fertility Holidays. Many of the 29 people in her study—conducted at two clinics in the Czech Republic between 2010 and 2011, with follow-up interviews in North America between 2011 and 2012—said they were put off by the ostentatiousness of the reproductive endocrinologists’ offices and what they saw as indifferent treatment from arrogant doctors. One participant noted she felt like a “walking ATM,” while respondents in both studies said they had been advised to remortgage their homes.

But on the internet, these couples—mostly white and from the lower-middle class—felt empowered as they researched new avenues of treatment. A 10-day to three-week trip to the Czech Republic for an IVF cycle costs just $10,000—with a vacation thrown in, to boot.

But as Speier notes, when patients become consumers, they take on an enormous burden, which can ultimately be disempowering.

“Despite the positive associations patients attribute to and experience in their usage of the internet, the fact remains that patients are unquestioningly accepting personal responsibility for their health care,” Speier writes. “Even more problematic, they must manage the risks associated with traveling abroad for IVF.”

Amy Speier looks at the burgeoning IVF tourism industry in her book Fertility Holidays

This time-consuming burden often falls on women, who—despite the fact that the medical causes are equally linked to both genders—are also seen as primarily shouldering the trials and tribulations of infertility.

Although cost doesn’t completely explain reproductive travel to the Czech Republic—the promise of white babies via anonymous egg donations plays a large role—Speier believes that the lower prices affected how the North Americans in her sample saw their experiences abroad.

“Being handed a huge bag of medications that in the United States would cost 10 times more and not being charged immediately was interpreted as care,” she says. “They would walk in to find the doctor waiting for them. They felt cared for.”

Because these patient-travelers didn’t feel nickel-and-dimed, they saw the Czech brokers and clinics as operating with purer motives. And because egg donation must be voluntary under Czech law, many chose to see the act as a gift. In fact, the compensation Czech donors receive for their discomfort is slightly higher than the country’s average monthly salary (though it’s still an eighth of what U.S. egg donors make).

“Given currency exchange rates, salary scales, and public investment in health care, services that appear ‘altruistically cheap’ and ‘humanely available’ by U.S. standards actually earned a profit in the Czech context,” Speier notes.

Despite dramatically lower prices abroad, fertility services are not cheap anywhere. Compelled by hope and cultural ideas about the necessity of family and the value of hard work, many couples keep trying new technologies, even as it leads them into debt or prompts them to make risky but cost-effective health care decisions.

Since there is currently little incentive for the industry to lower its prices, “it quickly becomes obvious that the economic reality of reproductive medicine in the United States exiles many patients,” Speier writes. “The lower-middle class is denied treatment options. Despite the fact that women keep trying, working hard to reach their goals of having a family, the system undermines their efforts, making treatment impossible and unaffordable.”

Jacobson believes this fundamental contradiction—between emphasizing parenthood yet not supporting it—speaks to who we are as a society.

“We valorize motherhood and yet we don’t make it easy at all for mothers in our society,” she says. “The United States has high rates of infant and maternal mortality compared to other industrialized nations today, and we have very low rates of supporting working mothers and working families. We don’t make it easy for people to have children in our society, but people work awfully hard at having families.”

In this excerpt from Fertility Holidays, Speier explains some of the factors that made the Eastern European country a hotbed for reproductive medicine.

Assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) have been a growing field (of medicine and business) in the Czech Republic since the 1990s. By the end of the twentieth century, 4,000 of all births in the Czech Republic were IVF births. In 2007, 5,000 cycles of IVF occurred in the Czech Republic, and this number is increasing. It is estimated that 15 percent of Czech couples suffer infertility, and 3.5 percent of Czech babies are born via assisted reproduction. […]

The Czech reproductive tourism industry is growing because of its low price structure and liberal legislation. Unlike its Catholic neighbors Slovakia and Poland, the Czech Republic is predominantly atheist. Given the Catholic Church’s strong influence over state regulations of assisted reproductive technologies, the relative lack of strong religious convictions in the Czech Republic allows for looser regulatory frameworks regarding ARTs. In June 2006, the Czech Republic passed legislation that governs sperm and oocyte donation. Under this legislation, donation is legal but must be voluntary, free, and anonymous. Donors cannot be paid directly for their eggs, but they are instead offered attractive “compensatory payments” for the discomfort involved in ovarian stimulation and egg retrieval. In a region where the average monthly salary was under 25,000 crowns (US $1,250) in 2011, donors receive roughly US $1,400 per egg donation. People have argued that in the case of gamete donation, without payment, there would simply not be any donors. Although they are fairly liberal, Czech clinics will treat only heterosexual, married couples. Only one of my North American informants was openly single.