FEATURE

STORIES

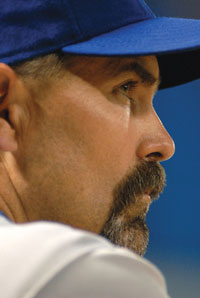

KC Masterpiece

Fiery yet compassionate, Manager Trey Hillman looks to return the Kansas City Royals to major league glory

he first time you see Trey Hillman, he doesn’t even know you’re there. Bedecked in Royal blue from cap to cleat, he makes a beeline through the batting cage strung across an immaculately manicured field, to a groundskeeper who has caught his eye. He hollers something about falling in the shower (must be an inside joke), comes apart in laughter (must be funny), and then vanishes again in a flash (must be busy).

He never sees you standing there as you shoot the breeze with his groundskeeper, asking about this palatial ballpark and how in the world you navigate it. Here is Trey Hillman in Surprise, Ariz., in the closing days of his first spring training as a big-league manager, unguarded, unreserved and unfiltered. Which, as you’re about to learn, is the Trey Hillman that every Kansas City Royal, from the general manager on down, has come to love.

When the 45-year-old UT Arlington graduate (’91 BA) became the Royals’ manager last October, he inherited a fading franchise: Kansas City lost 403 games in the last four seasons, hasn’t reached Major League Baseball’s postseason since 1985 and has a losing record in 14 of the last 15 years. Since their last playoff appearance, the Royals have tried 11 managers, only two of whom posted more than one winning season.

That history is history in the KC clubhouse these days. The team has an optimistic new administrative team, a roster of promising youngsters and sagacious veterans and a fun-but-focused philosophy fostered by a manager who’s a maverick in more ways than one.

Oneonta and Sapporo

Interesting how Hillman wound up in Kansas City. He has been around baseball most of his life and was one of the best hitters in UT Arlington history (his .442 batting average in 1985 remains a single-season record). When his playing career stalled in the minor leagues, he was named manager of the New York Yankees’ Class A team in Oneonta, N.Y. In that first season, he won a league title.

And found a calling.

He managed up and down the Yankees’ farm system for 12 seasons, compiling more than 850 wins and helping develop superstars Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera, Jorge Posada, Bernie Williams and Alfonso Soriano. He left the bench briefly to be the Texas Rangers’ player development director, but in 2003 he made a decision that would alter the path of his career and his life. Alter it due east.

In 2003 Hillman became manager of the Hokkaido Nippon Ham Fighters, a sad-sack team in Japan’s professional baseball league. When he arrived, the team was moving from Tokyo to Sapporo, and the franchise hadn’t won a championship in more than 40 years.

Still, he guided the Fighters to a playoff bid in just his second season. In his fourth, he brought home Japan Series and Asia Cup championships and became such an icon that a Hillman-themed restaurant opened in Sapporo, and fans sought even his children’s autographs. He earned notice back home, too, interviewing for managerial jobs with the Rangers, San Diego Padres and Oakland Athletics. Ultimately, he returned to Japan and led the Fighters back to the Japan Series.

Despite that success, he knew the 2007 season would be his last in Japan. Even though no job awaited in the states, he wanted to work closer to his wife and children in the Texas Hill Country. He figured he’d land a job somewhere in professional baseball.

Maybe not in the majors. And maybe not as a manager.

Hillman and Rangers Manager Ron Washington exchange lineups before a game.

Then Dayton Moore, the Royals’ fresh-faced general manager who was shopping for a new skipper, flew to Japan at the suggestion of his advisers. After 2½ days with Hillman, Moore had found his man.

“Instinctively, I felt very good about him being possibly our next manager,” Moore said. “I’d known his name for quite some time as somebody who had always won. He had a reputation for being very energetic, very prepared and very instinctive as a baseball man. So that’s what led us there.”

A week later, Hillman was the rare big-league manager who never played or coached in the majors. But, his players say, such experience can be overrated.

“Times have changed in a lot of ways,” says second baseman Mark Grudzielanek, a big leaguer since 1995. “Dayton Moore went outside the organization and wanted to get somebody fresh, somebody new, somebody young, somebody with fire, somebody who has had winning be a part of who they are.”

Or, as outfielder Mark Teahen puts it: “If you know the game, you know the game.”

Even if you learned it in places like Oneonta and Sapporo, Japan.

Building a winner

Hillman steps out of the Royals’ clubhouse and into the desiccating Arizona sun for another day of spring workouts. The press corps swarms, one camera only inches from his face. He leans coolly on a blue fungo bat, smacks down on a gob of Bazooka bubblegum and answers question after question as his players do calisthenics.

This may be his first major league spring training, but clearly he’s at ease. It’s also clear that he’s in charge.

Most managers focus on the October playoffs, but the dress rehearsal of March matters just as much to Hillman. To turn the Royals around, their new manager must stress pitching, fielding, scoring runs—the fundamentals.

Hillman is building a winning team where there hasn’t been one in a long time. George Brett believes he’s witnessing a Royals renaissance.

“He gives a simple explanation of what we’re trying to accomplish and how we’re going to accomplish it,” says Brett, the iconic Hall of Fame hitter who’s now the team’s vice president for baseball operations. “He explains things to the players very direct, very matter of fact, very common sense. … He stresses the fundamentals that I think everybody does, but he communicates it in a much easier way for the players to absorb it and believe it.”

Never was that more apparent than after one spring training game that Kansas City won in its last at-bat. As the players celebrated, the manager reminded them that such dramatics might not have been necessary had they run the bases better in earlier innings.

He’s that committed to winning, even when the games don’t count.

- Kansas City Royals Manager Trey Hillman ('91 BA)

“I mean, we’re 10-10 right now,” Hillman said in late March. “I know it’s only spring training in some people’s minds, but we’re playing games, and I want to win these games.”

Hours later, he sits literally on the edge of his seat as his Royals play an exhibition against the Milwaukee Brewers. It’s a meaningless scrap, and few in the ballpark seem to notice that it’s going on. Still, there will be a winner at night’s end, and Hillman expects it to be his Royals. And on this night it is, 11-4.

Last summer, the Royals finished near the bottom of most offensive statistical rankings; with a few exceptions, their lineup is unchanged this season, so 11 runs says something.

For starters, it says that Hillman means it when he vows, “We’ll find a way to score runs.” It says that his players buy into his philosophy of getting runners on, getting runners over, then getting runners in, and not waiting for a big home run.

Case in point: Kansas City opens the game with four soft singles, two walks, a sacrifice fly, a stolen base and a passed ball. The inning ends when infielder Tony Peña Jr., who needn’t worry about his place on the roster, grounds out but sprints hard toward first and lunges for the bag.

See, these games matter to Hillman’s players, too.

“He has fire, determination and high drive in practice as well as in games,” Grudzielanek says. “He expects you to do your best.”

The game beyond the game

Hillman is part baseball man, part businessman. That’s clear the moment Mike Swanson, the Royals’ vice president for communications, plops down on the oversized sofa that dominates Hillman’s spring training office.

Swanson needs the manager to talk with TV officials about which inning will feature Hillman’s in-game, on-air interviews. Tonight it’s the second, and Hillman scribbles a reminder on the palm of his hand. But he’s interrupted by his Blackberry that’s “lit up like a Christmas tree.” It’s Moore, the GM, and he wants a few minutes of Hillman’s time.

“This,” Swanson said, “is what it’s really like to be a major league manager.”

Hillman is accustomed to the grind. He’s awake by 3 a.m. most days, and to the field by 3:45. Alone at that hour, he’s free to reflect on his ballclub and the 22 possible lineups that hang above his desk. All spring, he and his staff have experimented with lineups to give veterans strategic days off and assess the players fighting for roster spots.

“Roster cuts are easily the most difficult days,” he says. “You’re telling people that right now, they’re not in your plans. I’ve been there. Those are difficult meetings, but the only thing you can do is tell the truth, give fair evaluations, and make sure guys know that you’ve done your best to give them a chance to make the club.”

His workday ends 16 hours after it begins, when “you just go home, try to get a good night’s sleep, then come back and do it again. That’s the only way I know how to do it.”

Hillman is known as a player's manager. "His people skills are off the chart," bench coach Dave Owen says.

He wants to make sure that players like Yasuhiko Yabuta have every chance. Yabuta, a young Japanese pitcher, says he’s honored to make his first foray into American baseball playing for a man he respected so much in Japan.

“I can’t understand the language,” Yabuta says through a translator, “so he talks to me in Japanese. He helps me a lot. He cares for me.”

Hillman, in baseball parlance, is a player’s manager. He pats his guys on the chest as he passes through the locker room, stopping to ask (speaking in Spanish to Latin players) how they’re doing and how they spent their recent off day.

“His people skills are off the chart,” says Dave Owen, the Royals’ bench coach and another UT Arlington alumnus. “He’s a man of tremendous integrity, and that alone sets the example for everybody else. He knows how to treat people.”

But let’s be clear. Hillman isn’t here to make friends. He loves his players, but he loves winning, too. “It doesn’t specifically say in the job description [or] in the actual contract you sign that you have to be geared to win a championship,” he says. “But I believe that that’s just something that goes with the territory. It’s the only way I know how to be geared. I want us to win, and I want to win now.”

He’ll support his players with everything he has. But he’ll still “kick them in the rear when they need it.”

A bright future

It’s less than two weeks before the season starts, and Grudzielanek, the star second baseman, is injured. A bad back has relegated him to designated hitter duties in minor league games, the far reaches of the baseball universe. But here he sits in the clubhouse, dressed in his civvies, with a smile on his face.

“We have high hopes,” he says. “We have the belief that this guy can turn this around. Why shouldn’t he? He’s a winner. He has won everywhere he’s been. … Good things will happen.”

Sitting on the opposite side of the room, but on the same side of the fence, is the young outfielder Teahen. “All of that winning [that Hillman has done] is going to pay off at some point. We’re going to learn how to win.”

If that proves true, it will be the next chapter in Hillman’s legacy. He won championships for the Yankees in baseball’s best minor leagues. He resuscitated a cellar-dwelling Japanese team. Now he’s trying to erase a culture of losing in Kansas City.

Trey Hillman is the common denominator, but he reminds you again and again that baseball is a team sport. It’s the Royals who will win, not Hillman. He doesn’t throw a pitch, snare a liner or swing a bat. He doesn’t assemble the team or write the checks. He simply pulls the levers that make it all work.

“We will win here,” he says, punching that first word. “We won in Japan. It wasn’t Trey Hillman. I don’t deny that it was my plan that we put together on the field, but it took a lot of people to implement the plan and a lot of loyalty and dedication to a foreign manager. When we win here, it won’t be Trey Hillman. It will be a collaborative effort of all the people Dayton Moore has put in place and who [owners] David and Dan Glass have allowed to work for the Royals.”

Hillman is intent on succeeding, no matter who gets the credit. He’s squarely focused on teaching players how to win, on building a dynasty, on turning Kansas City into baseball’s new title town.

As focused as he is, it’s easy to see why everyone believes in this man. And it’s easy to understand why when you first see him, he doesn’t even notice you standing there.

— Danny Woodward

Other Stories

Deep thinkers

Pilot projects encourage students to take charge of their own learning

Mavericks Personified: Wajiha Rizvi

Recent graduate takes a campaign detour

Family Friendly

Dan and Grace Cruz never dreamed they'd one day attend college alongside sons Mike and Nick. It's hectic but worth it, they all say.

Arctic exploration

Researchers examine Alaskan tundra for insight into climate warming

What’s in a name?

Building namesakes include former presidents, deans, coaches and an astronaut

Contact Us

Office of University Publications

502 S. Cooper St.279 Fine Arts Building

Box 19647

Arlington, TX 76019-0647