Punch Line

The Culture of Cartoons

Newspaper cartoons play a key role in debates about free speech, politics, and cultural expression across the globe By Dr. Ritu Gairola Khanduri, Associate Professor of Cultural Anthropology

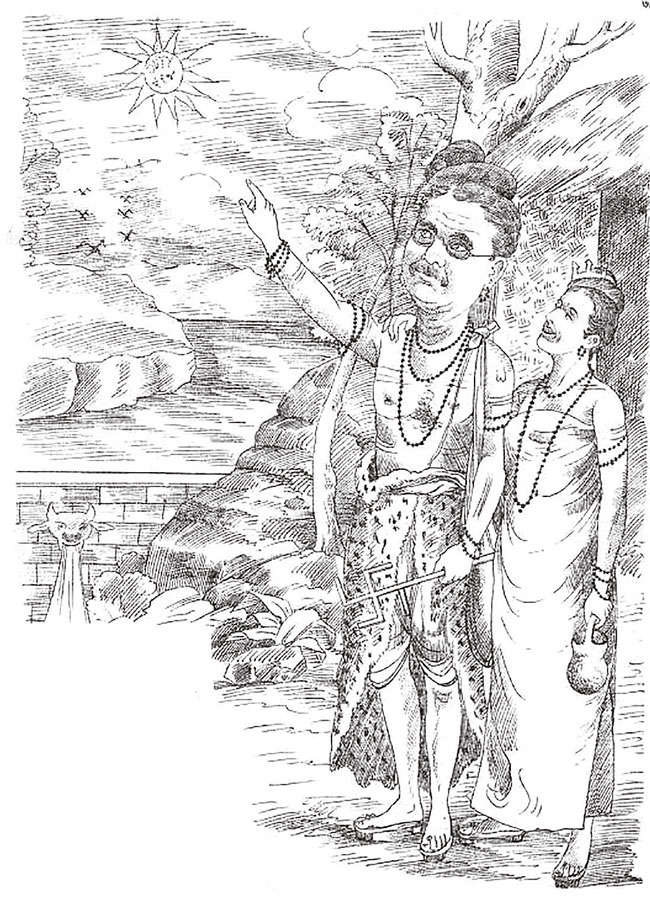

In colonial India, The Hindi Punch, modeled after the British humor magazine Punch, caricatured British officials and Indian nationalist leaders as Hindu gods and goddesses. (Note: The swastika, which in Sanskrit means “well-being,” has been a sacred symbol in Hinduism for thousands of years.)

More than any other art form, cartoons have the power to entice the public to engage with modern politics. With the assassination in January of cartoonists working for the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and the attack in Copenhagen a month later targeting artist Lars Vilks, this connection has become even more important. The issue at the root of both incidents is familiar—the limits, or lack thereof, of free speech.

With its rich history of political cartooning, India, the largest democracy in the world, can illuminate much about these politics of representation. The country’s fierce secularism and liberalism, combined with its socio-economic inequality, make for a complex political situation—one that requires flexibility in the name of cultural rights. This diversity shapes the parameters of cartooning, satire, and taking offense in the country.

My own journey into the world of cartooning began with a chance reading of an angry letter to the editor in the Times of India. The writer complained about a cartoon by the famous artist R.K. Laxman (1921-2015) that dealt with a recent, devastating earthquake. Until then, I hadn’t considered that cartoons could stir rebuke from the general public, not just elites and those in power (the groups most often lampooned). I began to trace evidence of offense generated by cartoons in colonial and contemporary India. This history can be a reference point for deliberations in other democracies, including the United States, where cartoons and satire frequently come under scrutiny for depicting racist and demeaning stereotypes.

As I sifted through archived reports detailing colonial surveillance of cartoonists, read through Gandhi’s opinions, and tracked petitions against cartoons in contemporary India, the world of cartoons began to take shape for me. This world does not always reverberate with peals of laughter at the sight of a cartoon; instead, it weighs in on the meaning of cartoons and sometimes dares to refuse to laugh. Cartoons are more than a form of dissent; they are a source for aesthetic evaluation, ethnocentric perspectives, and debate. As I detail in my book, Caricaturing Culture in India: Cartoons and History in the Modern World, colonial judgments on “native” cartoons—and their complaints about natives not having a sense of humor—provide a fascinating glimpse into how different ideas about humor were integral to the British Empire’s civilizational discourse.

The story of India’s democracy, its contents, and its discontents can best be chronicled through the cartoons that have been published in its daily newspapers. For example, Laxman’s popular character, the Common Man, pointed public attention toward the contradictions in developmental agendas and the paradox of democracy where inequality is commonplace. India boasts a significant number of cartoonists who deserve attention for holding democracy accountable with the strokes of their brushes and the points of their pens. And when the press in the country falters or is threatened, its members can seek recourse with the Press Council of India (PCI), a quasi-judicial body that mediates complaints and sets the norms for journalistic ethics. Readers also can register complaints against offensive cartoons, debate with newspaper representatives (including editors), and seek an apology or a withdrawal of a cartoon. In the framework of the PCI, cartoons are considered a “special category of news” and demand an ethics of representation.

This demand and practice of cartoon ethics in India can play a significant part in the ongoing discussions about the limits to free speech and the freedom of expression. In fact, cartoons have become indispensable to this discussion. And judging by history recent and distant, they will continue to be so.