Outlast

Ultimate Survivors

Scientists uncover importance of elemental carbon in rebuilding life after mass extinction

Layers of elemental carbon were found in the shells of marine organisms that survived mass extinction.

More than 252 million years ago, Earth experienced one of the greatest mass extinctions in its history. A new study led by UTA scientists demonstrates for the first time how elemental carbon became an important construction material for ocean life after that catastrophic event.

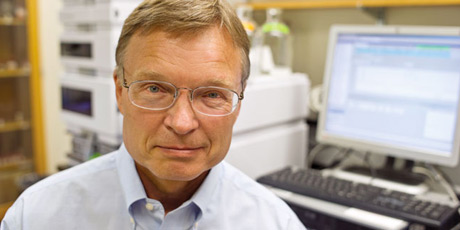

At the end of the Permian Period of the Paleozoic Era, more than 90 percent of terrestrial and marine species became extinct. According to the study’s co-author, earth and environmental sciences Professor Merlynd Nestell, there was extensive volcanic activity in both hemispheres during that time, as well as synchronous volcanic activity in what is now Australia and southern China that could have burned Permian vegetation.

“Much of the volcanic activity was connected with the Siberian flood basalt known as the Siberian Traps that emerged through Permian-aged coal deposits,” Dr. Nestell explains. “And of course, the burning of coal created carbon dioxide.”

For the study, researchers focused on a section of Permian-aged rocks in Vietnam just south of the Chinese border. There, Professor Emeritus Brooks Elwood collected closely spaced samples from a four-meter interval in the boundary strata for magnetic and geochemical properties.

The team discovered that the carbon from this ash accumulated in the atmosphere and marine environment and was used by some marine microorganisms in the composition of their shells—something they had never done before. These organisms included the single-celled agglutinated foraminifers, ostracodes, and worm tubes that made up part of the very limited population of bottom-dwelling marine organisms that survived the extinction event.

“Although black layers were revealed in specimens of the boundary-interval foraminifers seen in slices of rock, nobody really checked the composition of the black material,” explains Galina P. Nestell, study co-author and adjunct research professor of earth and environmental sciences.

The data the team collected and analyzed supports the presence of products of coal combustion that contributed to the high input of carbon into the marine environment immediately after the extinction event.

The team’s study was published in the March edition of International Geology Review.

Illustration by JING JING TSONG