The science of landscapes

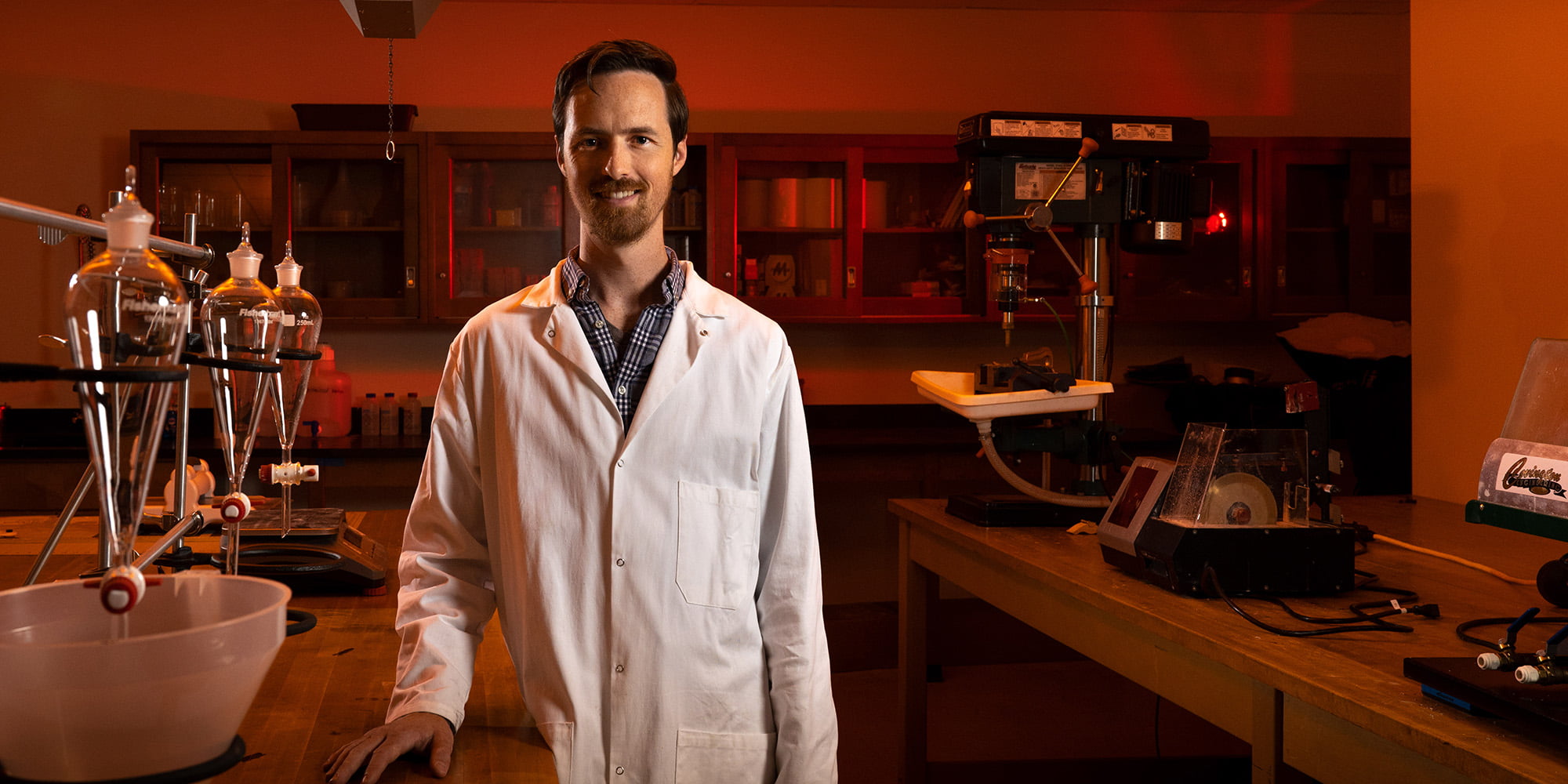

Nathan Brown, UTA assistant professor of Earth and environmental sciences, is kind of a storyteller.

A quaternary geochronologist — “It’s a mouthful,” Brown acknowledges — he studies grains of sediment to establish the ages of significant events in a landscape’s history. In doing so, he puts together a story of things that happened in the past and how they might happen again in the future.

While Brown spends time in the field collecting samples — around hydrothermal-explosion craters at Yellowstone National Park or around the San Andreas Fault lines, for example — the precise work of dating sediment samples takes place in his Dark Lab. That’s where he and his students determine the age of those samples based on when they were last exposed to light or heat, a process known as luminescence dating.

Karissa Cordero, a first-year doctoral student, began research in Brown’s lab as an undergraduate. Her very first lesson with Brown was a crash course in sample collection from two explosion craters in Yellowstone. Protecting the collected rocks and minerals from sunlight was of utmost importance.

“As soon as we extract the samples, we quickly wrap them in foil and pack them into black plastic bags,” Cordero said. “The samples must stay dark; otherwise, the luminescence signal is destroyed before we can examine it in the lab.”

As a geochronologist, Brown’s goal is to ensure that the story we tell about the landscape is correct.

“You know there can only be one story behind what happened, but you’re left with fragmentary clues,” he said. “You do your best to sort out what happened to produce the landscape we see today.”

In the Dark Lab, doctoral student Ayush Joshi crushes the bedrock samples he collected from the San Gabriel Mountains. Once the samples are crushed and sieved, he extracts feldspar, a group of minerals that emit the latent luminescence signals he needs to determine how quickly the southern California mountains are eroding. Under Brown’s instruction, he studies the evolution of landscapes surrounding the San Andreas Fault.

The results of Brown’s lab serve not only to give us a glimpse into the past, but also to provide insight into events that could happen in the future. In his work at Yellowstone, he’s helping to uncover when and where hydrothermal explosions could occur. Along the San Andreas Fault lines, he’s working to better understand earthquake activity — how it shapes the landscape and when it might happen again.

“The picture is always evolving as scientists learn how to take new measurements or gain additional insight into these processes,” he said. “Then the story changes slightly or you get a little bit more clarity, so we're always working toward this one story together.”

--

The UTA College of Science, a Texas Tier One and Carnegie R1 research institution, is preparing the next generation of leaders in science through innovative education and hands-on research and offers programs in Biology, Chemistry & Biochemistry, Data Science, Earth & Environmental Sciences, Health Professions, Mathematics, Physics and Psychology. To support educational and research efforts visit the giving page, or if you're a prospective student interested in beginning your #MaverickScience journey visit our future students page.