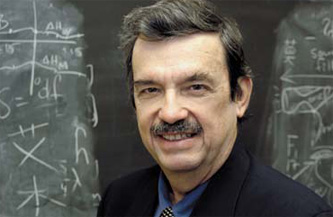

When Jerold Edmondson listens to you, he really listens.

The linguistics professor does more than focus on words as they create sentences and meaning. He studies how humans use vocal behaviors like pitch and voice quality as part of their language systems.

|

| Linguistics Professor Jerold Edmondson is an internationally recognized expert on the minority of languages of Southeast Asia. He has explored the limits of how humans use vocal behaviors such as pitch and voice quality as part of language systems. In the 1990s he discovered two previously unknown languages: Nung Ven and Xapho. |

Dr. Edmondson, who speaks eight languages, is internationally known for this research. For 25 years he has traveled to the ends of the earth to study a particular language and how it fits into the larger set of languages belonging to that family.

His research on the minority languages of Southeast Asia in the mid-1990s led to the remarkable discovery of two previously unreported languages: Nung Ven (distantly related to Thai) and Xapho (distantly related to Chinese).

“We were in northern Vietnam, near the China border, in the home province of one of the persons on our team,” he recalled. “This person said he had been up in the area before and heard a language called Nung Ven—meaning ‘the Nung with the ear rings,’ presumably because the women there wear big earrings. It shocked him that he couldn’t understand it, especially since he’s a speaker of the language closely related to it.”

After more research, Edmondson and his team discovered that the people spoke a cousin language of Thai.

“It was intriguing to find that this language had never been mentioned in Vietnam or any of the French sources we researched,” he said.

After Edmondson became interested in the Tibeto-Burman languages, he discovered Xapho.

“I was told there was not a single scholar in all of Vietnam who knew anything about Tibeto-Burman languages. But my readings and research into the languages of Vietnam told me there were some Tibeto-Burman languages.”

While visiting a marketplace village, he met a man who claimed to be a member of the “Xapho minority.” The meeting led Edmondson to a person who indeed spoke the unrecorded language.

The research, supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities, also provided data on several endangered languages, including one spoken by only two people in the Vietnamese borderlands.

“Language is a funny business,” said Edmondson, who concludes that research he has done on the missing teeth of the Dinkas is nothing short of “serendipitous.”

“I worked with a Dinka student back in the ’80s, so I knew a little about the Dinka language to begin with.” And when Edmondson began teaching English to Sudanese refugees in Arlington, his research took a turn.

“I had several students in my class who spoke six different languages—all from Sudan—the largest group being the Dinkas. And as it happens when you’re working with refugees, you become completely involved in their lives. You’re their caseworker, in a sense.

“These people were producing dramatic kinds of sounds that are not found in very many languages, so we wanted to know what it was. And we were able to do this with three Dinka speakers.”

Edmondson worked with specialists and other linguists using laryngoscopy, a procedure that utilizes cameras to look inside the nose and at the back of the throat, including the larynx and vocal cords.

Mary Willis, an anthropology professor at the University of Nebraska who was also doing Dinka research, heard about the work. Dr. Willis is studying the cultural, physical and nutritional ramifications of a Dinka rite of passage in which the four lower teeth are extracted.

“Lincoln, Nebraska, or Lancaster County, has perhaps the largest number of Sudanese refugees in the U.S.,” Edmondson explained, “most probably because the Dinka people are cattle herders, and there’s a large meat-packing industry in that area.”

Recently, Edmondson and Linguistics Department Chair David Silva teamed with Willis, who secured a grant from the Jacob and Valeria Langeloth Foundation that will allow some two dozen Dinkas living in Lincoln to receive dental implants.

“We’ve already been able to determine that the missing teeth make a difference in how they pronounce their native, or first, language,” Edmondson said. “But what we don’t know is whether the implants will fix the problem.”

Edmondson and Silva recently traveled to Lincoln when the Dinkas received their implants. The next step: examining the group after one year.

visit: https://ling.uta.edu/~jerry/

— Susan M. Slupecki

| Archives

| Alumni Association |

Giving to UTA | UTA

Home Copyright © 2006 UTA Magazine. All rights reserved. |