| Q&A with UTA's oldest living graduate | Alumni as college presidents | Recognition of contributors |

|

||

| Home Forethought Campus Buzz Feature Stories Re:Search The Score Alum News Yesteryear | ||

In Ronnie Liggett’s class, it helps to have a criminal mind. Or at least to get inside one.

Three days a week this spring, Liggett teaches an upper-level business course, Economics of Crime, where students use theories of economics “to explain criminal behavior ranging from white-collar crime to money laundering to prostitution.”

In other words, it’s not your typical U.S. government class that all students must take.

Economics of Crime, listed as ECON 3302, is just one UTA course that’s both distinctive and useful. Similar courses that offer creative curriculum but fit perfectly into a standard degree plan can be found in every college, school and department on campus. One geology course focuses on dinosaurs; architecture students can study the buildings of ancient Rome; a computer science class has students building their own robots; and young political scientists can dissect the political messages in everyday films.

“These courses illustrate how disciplinary knowledge can be applied in novel ways,” said Provost Dana Dunn, who notes that some offerings are unique to UTA while others, though they sound unusual, are standard parts of the curriculum at most universities. “The courses are appealing and can draw people to a particular discipline.”

Many universities offer unique courses based on faculty expertise and their geographic location. For example, an urban setting such as Arlington offers the perfect laboratory for social work, architecture and public administration. That Arlington is also home to Major League Baseball’s Texas Rangers, and soon the National Football League’s Dallas Cowboys, has piqued interest in the study of sports as academics.

|

COLORFUL CLASSES UTA offers more than 1,000 courses at the undergraduate and graduate level.Some are highly specialized but still help students progress toward their degrees. GEOL 3402 DINOSAURS HIST 3380 HISTORY OF ANCIENT SPORT ECON 3302 ECONOMICS OF CRIME CSE 4360 AUTONOMOUS ROBOT DESIGN AND PROGRAMMING SOCW 6361 STRESS, CRISIS AND COPING ANTH 5307 FORENSIC ANTHROPOLOGY POLS 4300 POLITICS IN FILM ARCH 5305 THE CITY OF ROME KINE 3307 SOCIOCULTURAL ASPECTS OF SPORT SOCI 3346 U.S. INTO THE 21ST CENTURY

|

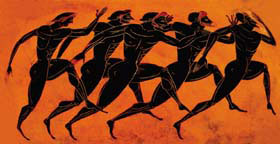

In kinesiology, within the College of Education, Lecturer Abu Yilla offers the Sociocultural Aspects of Sport course that examines sport’s place in American culture and “sociological dynamics as they relate to sport and exercise activities.” In history, in the College of Liberal Arts, department Chairman Don Kyle teaches History of Ancient Sport.

A niche has made Dr. Kyle a coveted authority on the ancient games—he’s been a consultant and on-camera interview for television documentaries worldwide. But he also faces challenges in teaching the class. Recent Hollywood films like Troy and Gladiator—Kyle calls them sword-and-sandal movies—“reinforce misguided notions about the Greeks and Romans.”

Further, he said, the media perpetuate myths about the ancient Olympics. Most textbooks don’t provide much material—a common problem in many of these highly specialized classes—and students typically have no familiarity with “the ancient world or with the problems of evidence one encounters in researching pre-modern history,” Kyle said. “Not to mention the difficulty students can have with near Eastern, Greek and Latin names and terms.”

Students may sign up for these intriguing courses because they believe they’ll be easy, Dr. Dunn said, while the opposite is true. Thus, the drop rate is often higher than average.

“These are serious courses,” Dunn said. “They’re not fluff or fun; they have real academic substance. They link to theory or theory and method so that the unique subject matter is embedded in an academic discipline. They’re not ‘pop’ classes for the general public.”

That’s especially true for Associate Professor Muriel Yu’s graduate-level social work course called Stress, Crisis, and Coping.

“The course covers basic health care social work,” she said. “The course is challenging because course contents are designed to cover specific topics for social work practitioners, and new research and literature are constantly being added to the field. But the course is actually fun to teach if students are highly motivated and particularly interested in entering the health care field.”

And as with most of these specialized classes, Dr. Yu’s class draws multidisciplinary interest. Though they’re usually upper-level courses—meaning they most often attract majors of that discipline—many prove to be popular electives.

Nursing students often enroll in Yu’s course. Kyle’s most recent ancient sports class drew 50 students from nine disciplines. Liggett has taught criminal justice and social work majors in his economics class, which sometimes numbers more than 170 students.

“Whether economic enthusiast or liberal arts major, there is much interest in discussing the specific economic and market forces that helped establish, for example, organized crime,” Liggett said. “Even if they (students from other majors) are initially a step behind in regard to economic knowledge, their diligence and approach to the class almost always enable them to do well.”

Sometimes diligence isn’t enough.

In Autonomous Robot Design and Programming, taught by computer science and engineering Assistant Professor Manfred Huber, a course described as “an introduction to robotics,” students must create three robot systems to solve an assigned task. The course includes two CSE prerequisites, plus knowledge of programming languages and kinematics, dynamics and control.

Dana Austin, an adjunct assistant professor who works full time for the Tarrant County Medical Examiner’s Office, teaches a course in forensic anthropology. Her students use case studies to learn to estimate a person’s age, sex and race based on skeletal remains. They’re learning from one of the best: Austin appeared on The Discovery Channel in February 2002 discussing a stagnated case she helped solve through her anthropological research.

Often, the challenging part for faculty who teach niche courses is making them applicable within a degree plan. Liggett said that’s also the fun part.

“Part of the beauty of this course is to be able to take controversial and serious topics such as gun control, illegitimacy and the death penalty, discuss them for social policy content, and then break them down in terms of economic theory,” he said. “Getting folks to discuss is rarely a problem.”

What’s tougher is getting them to think like a criminal.

— Danny Woodward

| Archives

| Alumni Association |

Giving to UTA | UTA

Home Copyright © 2005 UTA Magazine. All rights reserved. |