In his new book, The Apache Diaspora: Four Centuries of Displacement and Survival, history Associate Professor Paul Conrad brings to life the stories of displaced Apaches.

A young man walked the grounds of a school counting graves. He had been sent to Carlisle, Pennsylvania, in 1898 for an education, to be trained in welding, construction, and other industrial skills. As he passed through rows of gravestones, counting to 105 before he got “mixed up,” he learned other lessons. “Very few came back,” he observed.

Sam Kenoi was one who did, however. He slipped away one night on a westbound train and returned to his people. At this time, his Apache Indian relatives were U.S. prisoners of war and had been since the army rounded them up from their Arizona reservation in 1886 and shipped them into exile in Florida, Alabama, and then Oklahoma. Kenoi married and started a family. He settled on the Mescalero reservation in New Mexico after Apache POWs were finally freed in 1913 and given a choice of where to live. After his first wife died of pneumonia, he remarried and had more children. He organized his people in a bold effort to seek reparations for their 27-year internment.

Most lives are full of tragedy and triumph, and Kenoi’s was no exception. But his life was also particular, shaped by who he was as an Apache. Kenoi confronted challenges that his ancestors had faced for generations. How does one exist in a world that does not want you to exist as you are? How does one survive that which so many are not surviving? How does one start over in a foreign land or on land made foreign by colonialism? Kenoi responded to these questions creatively, pushed back on those who mistreated him, and lived boldly within the constraints of his circumstances.

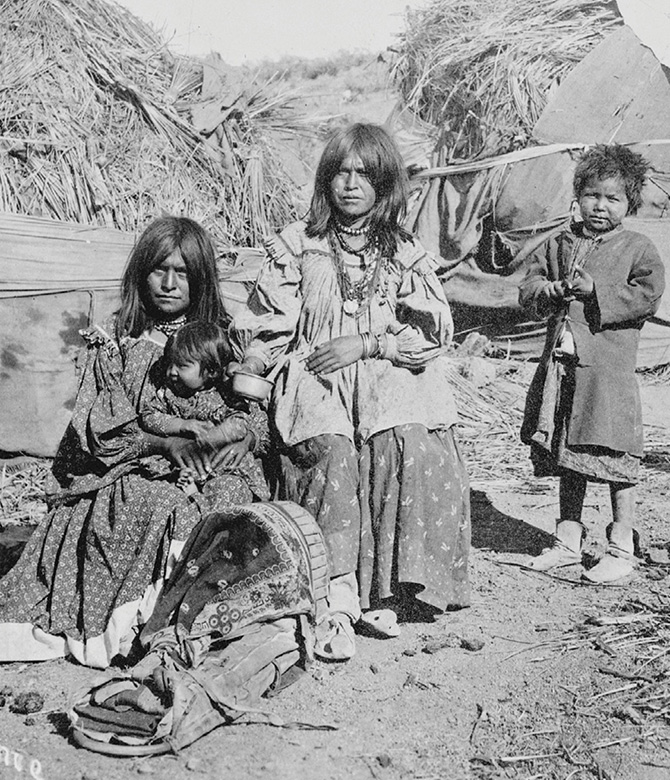

Pulling back from Kenoi’s particular story, a broader portrait of Apache life and death across North America and the Caribbean comes into view. Apache men and women throw themselves into the Gulf of Mexico, desperate to escape the boat waiting to carry them overseas. A priest pens an entry in a leather-bound ledger near the Pacific coast of Sonora—another Apache girl buried after months of forced labor. Apache boys run errands for the governor of Quebec, and Apache women gather water for their masters at a neighborhood well in Mexico City. Apache men pull a pine tree out of the chimney of an old U.S. fort in Florida and apply mortar to Spanish fortifications in the port of Havana. An Apache servant and a Black slave marry in a church in a Mexican mining town as a crowd of their friends looks on. Their children have children, who have children, their descendants still living across North America today. …

The history of the Apache diaspora reveals the efforts of outsiders to exploit, subjugate, or eliminate Indigenous people across more than four centuries, and Natives’ own determination to resist and survive wherever they have found themselves. Settler-citizens and imperial agents under Spanish, Mexican, and U.S. governments who believed themselves to be innovative often echoed one another, as they pursued failed but also destructive schemes to end Apache self-governance through enslavements and forced migrations that scattered Apaches across the continent. The ends and means of colonialism have shifted to some extent over time, but colonization and diaspora have not ended. They are ongoing, yet so too is Native resistance.